Sun, 05 Mar 2023 05:16:25 +0000

ABSTRACT

本ガイドライン群は, Digital Identity サービスを実装する連邦機関に対する技術的要件を提供するものであり, それ以外の条件下での標準仕様の開発・利用に対する制約を意図したものではない. 本ガイドラインは, 政府機関がネットワークを介して提供する情報システムを利用する Subject の Authentication にフォーカスしている. この Authentication により, 特定の Claimant が以前 Authenticate された Subscriber であるということが立証可能となる. Authentication プロセスの結果は Authentication を実行したシステムローカルで利用されることもあるが, Federated Identity System 内の別の場所で利用されることもある. 本ドキュメントは3つの Authenticator Assurance Level 毎に技術要件を定義する. 本ドキュメントの発行をもって, 本ドキュメントは既存の NIST Special Publication 800-63B を置き換えるものとする.

Keywords

authentication; authentication assurance; credential service provider; digital authentication; digital credentials; electronic authentication; electronic credentials; passwords.

翻訳者

- Hitomi Kimura

- Trend Micro Inc. (United States)

- Nov Matake

- OpenID Foundation Japan エバンジェリスト 兼 翻訳WGリーダー

- MoneyForward inc.

- YAuth.jp LLC

ABSTRACT

本ガイドライン群は, Digital Identity サービスを実装する連邦機関に対する技術的要件を提供するものであり, それ以外の条件下での標準仕様の開発・利用に対する制約を意図したものではない. 本ガイドラインは, 政府機関がネットワークを介して提供する情報システムを利用する Subject の Authentication にフォーカスしている. この Authentication により, 特定の Claimant が以前 Authenticate された Subscriber であるということが立証可能となる. Authentication プロセスの結果は Authentication を実行したシステムローカルで利用されることもあるが, Federated Identity System 内の別の場所で利用されることもある. 本ドキュメントは3つの Authenticator Assurance Level 毎に技術要件を定義する. 本ドキュメントの発行をもって, 本ドキュメントは既存の NIST Special Publication 800-63B を置き換えるものとする.

Keywords

authentication; authentication assurance; credential service provider; digital authentication; digital credentials; electronic authentication; electronic credentials; passwords.

Note to Reviewers

The rapid proliferation of online services over the past few years has heightened the need for reliable, equitable, secure, and privacy-protective digital identity solutions.

Revision 4 of NIST Special Publication 800-63 Digital Identity Guidelines intends to respond to the changing digital landscape that has emerged since the last major revision of this suite was published in 2017 — including the real-world implications of online risks. The guidelines present the process and technical requirements for meeting digital identity management assurance levels for identity proofing, authentication, and federation, including requirements for security and privacy as well as considerations for fostering equity and the usability of digital identity solutions and technology.

Taking into account feedback provided in response to our June 2020 Pre-Draft Call for Comments, as well as research conducted into real-world implementations of the guidelines, market innovation, and the current threat environment, this draft seeks to:

- Advance Equity: This draft seeks to expand upon the risk management content of previous revisions and specifically mandates that agencies account for impacts to individuals and communities in addition to impacts to the organization. It also elevates risks to mission delivery – including challenges to providing services to all people who are eligible for and entitled to them – within the risk management process and when implementing digital identity systems. Additionally, the guidance now mandates continuous evaluation of potential impacts across demographics, provides biometric performance requirements, and additional parameters for the responsible use of biometric-based technologies, such as those that utilize face recognition.

- Emphasize Optionality and Choice for Consumers: In the interest of promoting and investigating additional scalable, equitable, and convenient identify verification options, including those that do and do not leverage face recognition technologies, this draft expands the list of acceptable identity proofing alternatives to provide new mechanisms to securely deliver services to individuals with differing means, motivations, and backgrounds. The revision also emphasizes the need for digital identity services to support multiple authenticator options to address diverse consumer needs and secure account recovery.

- Deter Fraud and Advanced Threats: This draft enhances fraud prevention measures from the third revision by updating risk and threat models to account for new attacks, providing new options for phishing resistant authentication, and introducing requirements to prevent automated attacks against enrollment processes. It also opens the door to new technology such as mobile driver’s licenses and verifiable credentials.

- Address Implementation Lessons Learned: This draft addresses areas where implementation experience has indicated that additional clarity or detail was required to effectively operationalize the guidelines. This includes re-working the federation assurance levels, providing greater detail on trusted referees, clarifying guidelines on identity attribute validation sources, and improving address confirmation requirements.

NIST is specifically interested in comments on and recommendations for the following topics:

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

- Are emerging authentication models and techniques – such as FIDO passkey, verifiable credentials, and mobile driver’s licenses – sufficiently addressed and accommodated, as appropriate, by the guidelines? What are the potential associated security, privacy, and usability benefits and risks?

- Are the controls for phishing resistance as defined in the guidelines for AAL2 and AAL3 authentication clear and sufficient?

- How are session management thresholds and reauthentication requirements implemented by agencies and organizations? Should NIST provide thresholds or leave session lengths to agencies based on applications, users, and mission needs?

- What impacts would the proposed biometric performance requirements for this volume have on real-world implementations of biometric technologies?

General

- Is there an element of this guidance that you think is missing or could be expanded?

- Is any language in the guidance confusing or hard to understand? Should we add definitions or additional context to any language?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address privacy?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address equity?

- What equity assessment methods, impact evaluation models, or metrics could we reference to better support organizations in preventing or detecting disparate impacts that could arise as a result of identity verification technologies or processes?

- What specific implementation guidance, reference architectures, metrics, or other supporting resources may enable more rapid adoption and implementation of this and future iterations of the Digital Identity Guidelines?

- What applied research and measurement efforts would provide the greatest impact on the identity market and advancement of these guidelines?

Reviewers are encouraged to comment and suggest changes to the text of all four draft volumes of of the NIST SP 800-63-4 suite. NIST requests that all comments be submitted by 11:59pm Eastern Time on March 24, 2023. Please submit your comments to dig-comments@nist.gov. NIST will review all comments and make them available at the NIST Identity and Access Management website. Commenters are encouraged to use the comment template provided on the NIST Computer Security Resource Center website.

Note to Reviewers

The rapid proliferation of online services over the past few years has heightened the need for reliable, equitable, secure, and privacy-protective digital identity solutions.

Revision 4 of NIST Special Publication 800-63 Digital Identity Guidelines intends to respond to the changing digital landscape that has emerged since the last major revision of this suite was published in 2017 — including the real-world implications of online risks. The guidelines present the process and technical requirements for meeting digital identity management assurance levels for identity proofing, authentication, and federation, including requirements for security and privacy as well as considerations for fostering equity and the usability of digital identity solutions and technology.

Taking into account feedback provided in response to our June 2020 Pre-Draft Call for Comments, as well as research conducted into real-world implementations of the guidelines, market innovation, and the current threat environment, this draft seeks to:

- Advance Equity: This draft seeks to expand upon the risk management content of previous revisions and specifically mandates that agencies account for impacts to individuals and communities in addition to impacts to the organization. It also elevates risks to mission delivery – including challenges to providing services to all people who are eligible for and entitled to them – within the risk management process and when implementing digital identity systems. Additionally, the guidance now mandates continuous evaluation of potential impacts across demographics, provides biometric performance requirements, and additional parameters for the responsible use of biometric-based technologies, such as those that utilize face recognition.

- Emphasize Optionality and Choice for Consumers: In the interest of promoting and investigating additional scalable, equitable, and convenient identify verification options, including those that do and do not leverage face recognition technologies, this draft expands the list of acceptable identity proofing alternatives to provide new mechanisms to securely deliver services to individuals with differing means, motivations, and backgrounds. The revision also emphasizes the need for digital identity services to support multiple authenticator options to address diverse consumer needs and secure account recovery.

- Deter Fraud and Advanced Threats: This draft enhances fraud prevention measures from the third revision by updating risk and threat models to account for new attacks, providing new options for phishing resistant authentication, and introducing requirements to prevent automated attacks against enrollment processes. It also opens the door to new technology such as mobile driver’s licenses and verifiable credentials.

- Address Implementation Lessons Learned: This draft addresses areas where implementation experience has indicated that additional clarity or detail was required to effectively operationalize the guidelines. This includes re-working the federation assurance levels, providing greater detail on trusted referees, clarifying guidelines on identity attribute validation sources, and improving address confirmation requirements.

NIST is specifically interested in comments on and recommendations for the following topics:

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

- Are emerging authentication models and techniques – such as FIDO passkey, verifiable credentials, and mobile driver’s licenses – sufficiently addressed and accommodated, as appropriate, by the guidelines? What are the potential associated security, privacy, and usability benefits and risks?

- Are the controls for phishing resistance as defined in the guidelines for AAL2 and AAL3 authentication clear and sufficient?

- How are session management thresholds and reauthentication requirements implemented by agencies and organizations? Should NIST provide thresholds or leave session lengths to agencies based on applications, users, and mission needs?

- What impacts would the proposed biometric performance requirements for this volume have on real-world implementations of biometric technologies?

General

- Is there an element of this guidance that you think is missing or could be expanded?

- Is any language in the guidance confusing or hard to understand? Should we add definitions or additional context to any language?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address privacy?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address equity?

- What equity assessment methods, impact evaluation models, or metrics could we reference to better support organizations in preventing or detecting disparate impacts that could arise as a result of identity verification technologies or processes?

- What specific implementation guidance, reference architectures, metrics, or other supporting resources may enable more rapid adoption and implementation of this and future iterations of the Digital Identity Guidelines?

- What applied research and measurement efforts would provide the greatest impact on the identity market and advancement of these guidelines?

Reviewers are encouraged to comment and suggest changes to the text of all four draft volumes of of the NIST SP 800-63-4 suite. NIST requests that all comments be submitted by 11:59pm Eastern Time on March 24, 2023. Please submit your comments to dig-comments@nist.gov. NIST will review all comments and make them available at the NIST Identity and Access Management website. Commenters are encouraged to use the comment template provided on the NIST Computer Security Resource Center website.

Purpose

This section is informative.

本ドキュメントとそれと対をなす各ドキュメント [SP800-63], [SP800-63A], そして [SP800-63C] は, Digital Identity Service を実装する組織に向けた技術的ガイドラインを提供するものである.

このドキュメント, SP 800-63Bは, 3つの Authentication Assurance Levels (AALs) のそれぞれでのRemote User Authenticationのための Credential Service Providers (CSPs) に対する要件を提供するものである.

Purpose

This section is informative.

This publication and its companion volumes, [SP800-63], [SP800-63A], and [SP800-63C], provide technical guidelines to organizations for the implementation of digital identity services.

This document, SP 800-63B, provides requirements to credential service providers (CSPs) for remote user authentication at each of three authentication assurance levels (AALs).

Introduction

This section is informative.

Digital Authentication は, Digital Identity を主張するために使用される1つかそれ以上の Authenticator の有効性を判断するプロセスである. Authentication は, デジタル サービスにアクセスしようとしている Subject が,Authentication に使用される技術を制御していることを立証する. 再訪問の対象となるサービスの場合, Authentication に成功することは今日サービスにアクセスする Subject が以前サービスにアクセスした Subject と同じであるという合理的なリスクベースの保証を提供する.

Subscriber の進行中の Authentication は, Subscriber をそれらのオンライン アクティビティ (つまり, Subscriber Account) に関連付けるプロセスの中心である. Subscriber Authentication は, 特定のSubscriber Account に関連付けられた1つかそれ以上の Authenticator (SP 800-63 の一部の以前のバージョンでは Token と呼ばれる) を Claimant が制御していることを検証することによって実行される. Authentication の成功は, Pseudonymous または Non-Pseudonymous Identifierと, 選択に応じてその他の identity 情報が Relying Party (RP) に Assertion される.

このドキュメントでは, さまざまな Authentication Assurance Level (AAL) で使用される可能性がある, Authenticator の選択を含む Authentication プロセスのタイプに関する推奨事項を提供する. また紛失や盗難が発生した場合の失効を含む Authenticator のライフサイクルに関する推奨事項も提供する.

この技術ガイドラインは, Subject のネットワーク越しのシステムに対する Digital Authentication に適用される. デジタルアクセスに使用されるいくつかの Credential は物理アクセスの Authentication にも使用される場合があるが, 本ガイドラインは (例: 建物などへの) 物理アクセスに対する個人の Authentication には対応しない. この技術ガイドラインでは, Authentication プロトコルに参加する Federal システムとサービス プロバイダーが Subscriber に対して Authenticate されることも要求する.

AAL は, Authentication Transaction の強度を, 順序のあるカテゴリとして特徴づけることができる. より強力な Authentication (より高い AAL) は, 悪意のあるアクターが Authentication プロセスの転覆を成功させるために, より優れた能力を持ち, より大きなリソースを消費することを必要とする. より高い AAL での Authentication は, Attack のリスクを効果的に減らすことができる. 各 AAL の技術要件の概要を以下に示す. 特定の Normative Requirement についてはこのドキュメントの Sec. 4 と Sec. 5 を参照のこと.

Authentication Assurance Level 1: AAL1 は, Claimant が Subscriber Account に Bind された Authenticator を制御するというある程度の保証を提供する. AAL1 は, 利用可能な幅広い Authentication 技術を使用した Single-Factor または Multi-Factor の Authentication を必要とする. Authentication の成功には, Claimant がセキュアな Authentication プロトコルを介して Authenticator の所有と制御を証明する必要がある.

Authentication Assurance Level 2: AAL2 は, Claimant が Subscriber Account に Bind された1つかそれ以上の Authenticator を制御するという高い確信を提供する. セキュアな Authentication プロトコルを介して, 2つの異なる Authentication Factor の所有と制御の証明が必要である. AAL2 以上では, Approved な暗号技術が必要である.

Authentication Assurance Level 3: AAL3 は, Claimant が Subscriber Account に Bind された1つかそれ以上の Authenticator を制御するという非常に高い確信を提供する. AAL3 での Authentication は, 暗号プロトコルを介した Key の所有の証明に基づく. AAL3 Authentication は, ハードウェアベースの Authenticator と Phishing 耐性のある Authenticator を必要とし(Sec. 5.2.5 を参照), 同じデバイスがこれらの両方の要件を満たす場合がある. AAL3 で Authentication を行うには, Claimant は, セキュアな Authentication プロトコルを介して, 2つのはっきりと異なる Authentication Factor の所有と制御を証明する必要がある. Approved な暗号技術が必要である.

次のリストは, ドキュメントのどのセクションが Normative で, どのセクションが Informative であるかを示す.

- 1 Purpose Informative

- 2 Introduction Informative

- 3 Definitions and Abbreviations Informative

- 4 Authentication Assurance Levels Normative

- 5 Authenticator and Verifier Requirements Normative

- 6 Authenticator Lifecycle Management Normative

- 7 Session Management Normative

- 8 Threat and Security Considerations Informative

- 9 Privacy Considerations Informative

- 10 Usability Considerations Informative

- 11 Equity Considerations Informative

- References Informative

- Appendix A Strength of Memorized Secrets Informative

- Appendix B Change Log Informative

Introduction

This section is informative.

Digital authentication is the process of determining the validity of one or more authenticators used to claim a digital identity. Authentication establishes that a subject attempting to access a digital service is in control of the technologies used to authenticate. For services in which return visits are applicable, successfully authenticating provides reasonable risk-based assurances that the subject accessing the service today is the same as the one who accessed the service previously.

The ongoing authentication of subscribers is central to the process of associating a subscriber with their online activity (i.e., with their subscriber account). Subscriber authentication is performed by verifying that the claimant controls one or more authenticators (called tokens in some earlier versions of SP 800-63) associated with a given subscriber account. A successful authentication results in the assertion of a pseudonymous or non-pseudonymous identifier and optionally other identity information to the relying party (RP).

This document provides recommendations on types of authentication processes, including choices of authenticators, that may be used at various authentication assurance levels (AALs). It also provides recommendations on the lifecycle of authenticators, including revocation in the event of loss or theft.

This technical guideline applies to digital authentication of subjects to systems over a network. It does not address the authentication of a person for physical access (e.g., to a building), though some credentials used for digital access may also be used for physical access authentication. This technical guideline also requires that federal systems and service providers participating in authentication protocols be authenticated to subscribers.

The AAL characterizes the strength of an authentication transaction as an ordinal category. Stronger authentication (a higher AAL) requires malicious actors to have better capabilities and to expend greater resources in order to successfully subvert the authentication process. Authentication at higher AALs can effectively reduce the risk of attacks. A high-level summary of the technical requirements for each of the AALs is provided below; see Sec. 4 and Sec. 5 of this document for specific normative requirements.

Authentication Assurance Level 1: AAL1 provides some assurance that the claimant controls an authenticator bound to the subscriber account. AAL1 requires either single-factor or multi-factor authentication using a wide range of available authentication technologies. Successful authentication requires that the claimant prove possession and control of the authenticator through a secure authentication protocol.

Authentication Assurance Level 2: AAL2 provides high confidence that the claimant controls one or more authenticators bound to the subscriber account. Proof of possession and control of two different authentication factors is required through secure authentication protocols. Approved cryptographic techniques are required at AAL2 and above.

Authentication Assurance Level 3: AAL3 provides very high confidence that the claimant controls one or more authenticators bound to the subscriber account. Authentication at AAL3 is based on proof of possession of a key through a cryptographic protocol. AAL3 authentication requires a hardware-based authenticator and a phishing-resistant authenticator (see Sec. 5.2.5); the same device may fulfill both these requirements. In order to authenticate at AAL3, claimants are required to prove possession and control of two distinct authentication factors through secure authentication protocols. Approved cryptographic techniques are required.

The following list states which sections of the document are normative and which are informative:

- 1 Purpose Informative

- 2 Introduction Informative

- 3 Definitions and Abbreviations Informative

- 4 Authentication Assurance Levels Normative

- 5 Authenticator and Verifier Requirements Normative

- 6 Authenticator Lifecycle Management Normative

- 7 Session Management Normative

- 8 Threat and Security Considerations Informative

- 9 Privacy Considerations Informative

- 10 Usability Considerations Informative

- 11 Equity Considerations Informative

- References Informative

- Appendix A Strength of Memorized Secrets Informative

- Appendix B Change Log Informative

Definitions and Abbreviations

定義と略語の完全な組み合わせについては [SP800-63] Appendix A を参照.

Definitions and Abbreviations

See [SP800-63], Appendix A for a complete set of definitions and abbreviations.

Authentication Assurance Levels

This section is normative.

与えられた AAL の要件を満たし, Subscriber として認識されるためには, Claimant は, そのレベルの要件と同等, またはそれ以上の強度のプロセスで Authenticate されることとする(SHALL). Authentication プロセスの結果は, Subscriber がその RP に対して Authentication する, それぞれの回で使用されることになる(SHALL) Identifier である. Identifier は Pseudonymous であってもよい(MAY). Subscriber Identifier は別の Subject に再利用されないほうがよい(SHOULD NOT)が, 以前に登録された Subject が CSP によって再登録された場合に再利用する必要がある(SHOULD). Subscriber を一意の Subject として識別するその他の属性も提供されることがある(MAY).

各 AAL での Authenticator と Verifier の詳細な Normative Requirement は Sec. 5 で提供される.

最も適切な AAL を選択する方法の詳細については [SP800-63] Sec. 5 を参照.

[FIPS140] 要件は, FIPS 140-3 か, それ以降のリビジョンで満たされる.

Identity Proofing の最中およびその後に収集された Personal Information は, Digital Identity サービスを介して Subscriber が利用できるようにしてもよい(MAY). 連邦政府機関によって任意の PII またはその他の Personal Information が開示されたりオンラインで利用可能になる場合, その情報が Self-asserted か Validated かにかかわらず, [EO13681] に従って Multi-Factor Authentication が要求される. したがって連邦政府機関は, PII またはその他の Personal Information をオンラインで利用可能にする場合には, 最低限 AAL2 を選択することになる(SHALL).

Authentication Assurance Level 1

AAL1 は, Claimant が Subscriber Account に Bind された Authenticator を制御するというある程度の保証を提供する. AAL1 は, 利用可能な幅広い Authentication 技術を使用した Single-Factor または Multi-Factor の Authentication を必要とする. Authentication の成功には, Claimant がセキュアな Authentication プロトコルを介して Authenticator の所有と制御を証明する必要がある.

Permitted Authenticator Types

AAL1 Authentication は, Sec. 5で定義されているいずれかの Authenticator タイプを使用することで発生することになる(SHALL).

- Memorized secret (Sec. 5.1.1)

- Look-Up secret (Sec. 5.1.2)

- Out-of-band device (Sec. 5.1.3)

- Single-factor one-time password (OTP) device (Sec. 5.1.4)

- Multi-factor OTP device (Sec. 5.1.5)

- Single-factor cryptographic software (Sec. 5.1.6)

- Single-factor cryptographic device (Sec. 5.1.7)

- Multi-factor cryptographic software (Sec. 5.1.8)

- Multi-factor cryptographic device (Sec. 5.1.9)

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

AAL1 で使用される Cryptographic Authenticator は Approved な暗号を使用することになる(SHALL). オペレーティングシステムのコンテキスト内で動作する Software-Based Authenticator は, 可能な場合, それらが実行中のユーザーエンドポイントで(例: マルウェアによる)侵害の検出を試みてもよい(MAY). また, そのような侵害が検出された場合は操作を完了しないほうがよい(SHOULD NOT).

Claimant と Verifier の間の通信は, Authenticator Output の Confidentiality (機密性) と Adversary-in-the-Middle (AitM) Attack への耐性の提供のため, Authenticated Protected Channel を介して行われることになる(SHALL).

連邦政府機関によって, または連邦政府機関に代わって AAL1 で運用されている Verifier は, [FIPS140] Level 1 の要件に適合しているか検証されることになる(SHALL).

Reauthentication

Subscriber Session の定期的な Reauthentication は, Sec. 7.2 で説明される通りに実行されることになる(SHALL). AAL1 では, Subscriber の Reauthentication は, ユーザーのアクティビティに関係なく, 延長使用 Session の間は少なくとも30日に1回繰り返される必要がある(SHOULD).

Security Controls

CSP は, [SP800-53] または同等の連邦 (例: [FEDRAMP]) ないし業界標準で定義されたベースラインセキュリティコントロールから適切に調整されたセキュリティコントロールを採用することになる(SHALL). 参考とするガイドラインは, 保護する対象となる情報システム, アプリケーション, オンラインサービスのために組織が決定すること. CSP は, 適切なシステムまたは同等のシステムに対する最低限の assurance-related controls が満たされていることを保証することになる(SHALL).

Records Retention Policy

CSP は, 適用される可能性のある National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) の記録保持スケジュールを含む, 適用される法律, 規制, およびポリシーに従って, それぞれの記録保持ポリシーを遵守することになる(SHALL). CSP が必須要件がない場合に記録を保持することを選択した場合, CSP は, 記録を保持する期間を決定するためにプライバシーおよびセキュリティリスクのアセスメントを含むリスク管理プロセスを実施することになる(SHALL). また, そのリテンションポリシーを Subscriber へ通知することになる(SHALL).

Authentication Assurance Level 2

AAL2 は, Claimant が Subscriber Account に Bind された Authenticator を制御するという高い確信を提供する. セキュアな Authentication プロトコルを介して, 2つの明確に異なる Authentication Factor の所有と制御の証明が必要である. AAL2 以上では, Approved な暗号技術が必要である.

Permitted Authenticator Types

AAL2 Authentication は, Multi-Factor Authenticator か, 2つの Single-Factor Authenticator の組み合わせのいずれかを使用することで発生することになる (SHALL). Multi-Factor Authenticator は, 単一の Authentication イベントを実行するために2つの要素を必要とする. 例として, デバイスを Activate するために必要となる Biometric センサーが統合された暗号的にセキュアなデバイスなどが挙げられる. Authenticator の要件は Sec. 5 に指定されている.

Multi-Factor Authenticator が使用されるとき, 以下のいずれかが使用されてもよい(MAY).

- Multi-Factor Out-of-Band Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.3.4)

- Multi-Factor OTP Device (Sec. 5.1.5)

- Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software (Sec. 5.1.8)

- Multi-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.9)

2つの Single-Factor Authenticator の組み合わせが使用されるとき, その組み合わせは, 以下のリストから1つの Memorized Secret Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.1) と 1つの物理 Authenticator (すなわち, “something you have”) を含むことになる(SHALL).

- Look-Up Secret (Sec. 5.1.2)

- Out-of-Band Device (Sec. 5.1.3)

- Single-Factor OTP Device (Sec. 5.1.4)

- Single-Factor Cryptographic Software (Sec. 5.1.6)

- Single-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.7)

Note: Biometric Authentication が Sec. 5.2.3 の要件を満たすとき, Biometric の一致に加えて, デバイスが Authenticate されなければならない. Biometric の特徴は1つの要素として認識されるが, それ自体は Authenticator とは認識されない. したがって, Biometric の特徴による Authentication を行う場合, 関連付けられたデバイスは “something you have” として働き, 同時に Biometric の一致は “something you are” として働くため, 2つの Authenticator を使用することは不要である.

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

AAL2 で使用される Cryptographic Authenticator は Approved Cryptography を使用することになる(SHALL). 連邦政府機関によって調達された Authenticator は [FIPS140] Level 1 の要件に適合していることを検証されることになる(SHALL). オペレーティングシステムのコンテキスト内で動作する Software-Based Authenticator は, 可能な場合, それらが実行中のプラットフォームで(例: マルウェアによる)侵害の検出を試みてもよい(MAY). また, そのような侵害が検出された場合は操作を完了しないべきである (SHOULD NOT). AAL2 で使用される少なくとも1つの Authenticator は, Sec. 5.2.8 で説明されているように, リプレイ耐性を持つことになる(SHALL). AAL2 での Authentication は, Sec. 5.2.9 で説明されているように, 少なくとも1つの Authenticator から Authentication Intent を実施する必要がある(SHOULD).

Claimant と Verifier の間の通信は, Authenticator Output の Confidentiality (機密性) と AitM Attack への耐性の提供のため, Authenticated Protected Channel を介して行われることになる(SHALL).

連邦政府機関によって, または連邦政府機関に代わって AAL2 で運用されている Verifier は, [FIPS140] Level 1 の要件に適合しているか検証されることになる(SHALL).

AAL2 での Authentication に Bimetric Factorが使用される場合, Sec. 5.2.3 で述べられるパフォーマンス要件を満たすことになり(SHALL), Verifier は Bometric センサーとその後の Processing がこれらの要件を満たしていることを判断するべきである(SHOULD).

OMB Memorandum [M-22-09] は, 連邦政府機関に対して AAL2 のパブリックユーザーに少なくとも1つの Phishing 耐性のある Authenticator のオプションを提供することを要求している. Sec. 5.2.5 で説明されている Phishing 耐性は通常 AAL2 での Authentication には必要とされないが, Phishing は重大な脅威ベクトルであるため, Verifier は可能な限り AAL2 での Phishing 耐性のある Authenticator の使用を奨励するべきである(SHOULD).

Reauthentication

Subscriber Session の定期的な Reauthentication は, Sec. 7.2 で説明される通りに実行されることになる(SHALL). AAL2 では, Subscriber の Authentication は, ユーザーのアクティビティに関係なく, 延長使用 Session の間は少なくとも12時間に1回繰り返されることになる(SHALL). Subscriber の Reauthentication は, 30分以上続く非アクティブ期間の後に繰り返されることになる(SHALL). これらのタイムリミットのいずれかに到達した場合, Session は終了(つまり, ログアウト)されることになる(SHALL).

タイムリミットにまだ到達していない Session の Reauthentication には, Memorized Secret またはまだ有効な Session Secret と組み合わせた Biometric のみが必要とされるとしてもよい(MAY). Verifier は, 非アクティブタイムアウトの直前に, アクティビティを行うようにユーザーを促してもよい(MAY).

Security Controls

CSP は, [SP800-53] または同等の連邦 (例: [FEDRAMP]) ないし業界標準で定義されたベースラインセキュリティコントロールから適切に調整されたセキュリティコントロールを採用することになる(SHALL). 参考とするガイドラインは, 保護する対象となる情報システム, アプリケーション, オンラインサービスのために組織が決定すること. CSP は, 適切なシステムまたは同等のシステムに対する最低限の assurance-related controls が満たされていることを保証することになる(SHALL).

Records Retention Policy

CSP は, 適用される可能性のある NARA の記録保持スケジュールを含む, 適用される法律, 規制, およびポリシーに従って, それぞれの記録保持ポリシーを遵守することになる(SHALL). CSP が必須要件がない場合に記録を保持することを選択した場合, CSP は, 記録を保持する期間を決定するためにプライバシーおよびセキュリティリスクのアセスメントを含むリスク管理プロセスを実施することになる(SHALL). また, そのリテンションポリシーを Subscriber へ通知することになる(SHALL).

Authentication Assurance Level 3

AAL3 は, Claimant が Subscriber Account に Bind された Authenticator を制御するという非常に高い確信を提供する. AAL3 での Authentication は, 暗号プロトコルを介した Key の所有の証明に基づく. ハードウェアベースの Authenticator とPhishing 耐性のある Authenticator を使用することになり(SHALL), 同じデバイスがこれらの両方の要件を満たしてもよい(MAY). AAL3 で Authentication を行うには, Claimant は, セキュアな Authentication プロトコルを介して, 2つのはっきりと異なる Authentication Factor の所有と制御を証明することになる(SHALL). Approved な暗号技術が必要である.

Permitted Authenticator Types

AAL3 Authentication は, Sec. 4.3 の要件を満たす Authenticator の組み合わせのうちのひとつを使用することで発生することになる(SHALL). 可能性のある組み合わせは:

- Multi-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.9)

- Single-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.7) used in conjunction with a Memorized Secret (Sec. 5.1.1)

- Multi-Factor OTP device (software or hardware) (Sec. 5.1.5) used in conjunction with a Single-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.7)

- Multi-Factor OTP device (hardware only) (Sec. 5.1.5) used in conjunction with a Single-Factor Cryptographic Software (Sec. 5.1.6)

- Single-Factor OTP device (hardware only) (Sec. 5.1.4) used in conjunction with a Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.8)

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

Claimant と Verifier の間の通信は, Authenticator Output の Confidentiality (機密性) と AitM Attack への耐性の提供のため, Authenticated Protected Channel を介して行われることになる(SHALL). AAL3で使用される少なくとも1つの Authenticator は, Sec. 5.2.5 で説明されているよ うにPhishing 耐性があり(SHALL), Sec. 5.2.8 で説明されているようにリプレイ耐性があることになる(SHALL). AAL3 でのすべての Authentication と Reauthentication は, Sec. 5.2.9 で説明されているように, 少なくとも1つの Authenticator から Authentication Intent を示す必要がある(SHOULD).

AAL3 で使用される Multi-factor Authenticator は, [FIPS140] レベル 2 以上で検証されたハードウェア暗号モジュールか, 少なくとも [FIPS140] レベル 3 を全体的に上回る物理セキュリティとなる(SHALL). AAL3 で使用される Single-factor Cryptographic Device は, [FIPS140] レベル 1 で検証されるか, 少なくとも [FIPS140] レベル 3 を全体的に上回る物理セキュリティとなる(SHALL).

AAL3 の Verifier は, [FIPS140] レベル 1 かそれ以上で検証されることになる(SHALL).

AAL3 の Verifier は, Sec. 5.2.7 で説明されているように, 少なくとも1つの Authentication Factor に関して, Verifier の危殆化耐性があることになる(SHALL).

AAL3 のハードウェアベースの Authenticator と Verifier は, 関連する Side-Channel Attack (例: タイミングや消費電力の分析) に resist する必要がある(SHOULD).

AAL3 での Authentication に Biometric Factor が 使用される場合, Verifier は Bometric Sensor とその後の Processing が Sec. 5.2.3 で述べられるパフォーマンス要件を満たしていることを判断することになる(SHALL).

Reauthentication

Subscriber Session の定期的な Reauthentication は, Sec. 7.2 で説明される通りに実行されることになる(SHALL). AAL3 では, Sec. 7.2で説明される通り, Subscriber の Authentication は, ユーザーのアクティビティに関係なく, 延長使用 Session の間は少なくとも12時間に1回繰り返されることになる(SHALL). Subscriber の Reauthentication は, 15分以上続く非アクティブ期間の後に繰り返されることになる(SHALL). Reauthentication は両方の Authentication Factor を使用することになる(SHALL). これらのタイムリミットのいずれかに到達した場合, Session は終了(つまり, ログアウト)されることになる(SHALL). Verifier は, 非アクティブタイムアウトの直前に, アクティビティを行うようにユーザーを促してもよい(MAY).

Security Controls

CSP は, [SP800-53] または同等の連邦 (例: [FEDRAMP]) ないし業界標準で定義されたベースラインセキュリティコントロールから適切に調整されたセキュリティコントロールを採用することになる(SHALL). 参考とするガイドラインは, 保護する対象となる情報システム, アプリケーション, オンラインサービスのために組織が決定すること. CSP は, 適切なシステムまたは同等のシステムに対する最低限の assurance-related controls が満たされていることを保証することになる(SHALL).

Records Retention Policy

CSP は, 適用される可能性のある NARA の記録保持スケジュールを含む, 適用される法律, 規制, およびポリシーに従って, それぞれの記録保持ポリシーを遵守することになる(SHALL). CSP が必須要件がない場合に記録を保持することを選択した場合, CSP は, 記録を保持する期間を決定するためにプライバシーおよびセキュリティリスクのアセスメントを含むリスク管理プロセスを実施することになる(SHALL). また, そのリテンションポリシーを Subscriber へ通知することになる(SHALL).

Privacy Requirements

CSP は, [SP800-53] または同等の業界標準で定義された, 適切に誂えられたプライバシーコントロールを採用することになる(SHALL).

CSP が Identity Proofing, Authentication, Attribute Assertion (総称して “Identity Service”), 関連する不正行為の軽減, または法律や法的手続きの遵守以外の目的で Attribute を処理する場合, CSP は 追加の処理から生じるプライバシーのリスクに見合った Predictability と Manageability を維持するための手段を実装することになる(SHALL). 手段には, 明確な通知の提供, Subscriber の同意の取得, Attribute の選択的な使用・開示の有効化を含んでもよい(MAY). CSP が同意を手段として使用する場合, CSP は追加の処理の同意を Identity Service の条件にしてはならない(SHALL NOT).

CSP が政府機関であるか民間セクターの Provider であるかに関わらず, Authentication Service を提供または使用する連邦政府機関には, 以下の要件が適用される:

- 政府機関は, Senior Agency Official for Privacy (SAOP) と相談し, Authenticator を発行または維持するための PII の収集が [PrivacyAct] (Sec. 9.4 を参照) の要件をトリガーするかどうか判断するために分析を実施することになる(SHALL).

- 政府機関は, 該当する場合, そのような収集を対象とする System of Records Notice (SORN) を公開することになる(SHALL).

- 政府機関は, SAOP と相談し, Authenticator を発行または維持するための PII の収集が E-Government Act of 2002 [E-Gov].の要件をトリガーするかどうか判断するために分析を実施することになる(SHALL).

- 政府機関は, 該当する場合, そのような収集を対象とする Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) を公開することになる(SHALL).

Summary of Requirements

Table 1 は, 各 AAL の要件の non-normative な要約を提供する.

Table 1 AAL Summary of Requirements

| Requirement | AAL1 | AAL2 | AAL3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permitted authenticator types | Memorized Secret; Look-up Secret; Out-of-Band; SF OTP Device; MF OTP Device; SF Crypto Software; SF Crypto Device; MF Crypto Software; MF Crypto Device | MF Out-of-Band; MF OTP Device; MF Crypto Software; MF Crypto Device; or Memorized Secret plus: Look-up Secret, Out-of-Band, SF OTP Device, SF Crypto Software, SF Crypto Device | MF Crypto Device; SF Crypto Device plus Memorized Secret; SF OTP Device plus MF Crypto Device or Software; SF OTP Device plus SF Crypto Software plus Memorized Secret |

| FIPS 140 validation | Level 1 (Government agency verifiers) | Level 1 (Government agency authenticators and verifiers) | Level 2 overall (MF authenticators) Level 1 overall (verifiers and SF Crypto Devices) Level 3 physical security (all authenticators) |

| Reauthentication | 30 days | 12 hours or 30 minutes inactivity; one authentication factor | 12 hours or 15 minutes inactivity; both authentication factors |

| Security controls | [SP800-53] Low Baseline (or equivalent) | [SP800-53] Moderate Baseline (or equivalent) | [SP800-53] High Baseline (or equivalent) |

| AitM resistance | Required | Required | Required |

| Phishing resistance | Not required | Recommended | Required |

| Verifier-compromise resistance | Not required | Not required | Required |

| Replay resistance | Not required | Required | Required |

| Authentication intent | Not required | Recommended | Required |

Authentication Assurance Levels

This section is normative.

To satisfy the requirements of a given AAL and be recognized as a subscriber, a claimant SHALL be authenticated with a process whose strength is equal to or greater than the requirements at that level. The result of an authentication process is an identifier that SHALL be used each time that subscriber authenticates to that RP. The identifier MAY be pseudonymous. Subscriber identifiers SHOULD NOT be reused for a different subject but SHOULD be reused when a previously enrolled subject is re-enrolled by the CSP. Other attributes that identify the subscriber as a unique subject MAY also be provided.

Detailed normative requirements for authenticators and verifiers at each AAL are provided in Sec. 5.

See [SP800-63] Sec. 5 for details on how to choose the most appropriate AAL.

[FIPS140] requirements are satisfied by FIPS 140-3 or newer revisions.

Personal information collected during and subsequent to identity proofing MAY be made available to the subscriber by the digital identity service. The release or online availability of any PII or other personal information, whether self-asserted or validated, by federal government agencies requires multi-factor authentication in accordance with [EO13681]. Therefore, federal government agencies SHALL select a minimum of AAL2 when PII or other personal information is made available online.

Authentication Assurance Level 1

AAL1 provides some assurance that the claimant controls an authenticator bound to the subscriber account. AAL1 requires either single-factor or multi-factor authentication using a wide range of available authentication technologies. Successful authentication requires that the claimant prove possession and control of the authenticator through a secure authentication protocol.

Permitted Authenticator Types

AAL1 authentication SHALL occur by the use of any of the following authenticator types, which are defined in Sec. 5:

- Memorized secret (Sec. 5.1.1)

- Look-Up secret (Sec. 5.1.2)

- Out-of-band device (Sec. 5.1.3)

- Single-factor one-time password (OTP) device (Sec. 5.1.4)

- Multi-factor OTP device (Sec. 5.1.5)

- Single-factor cryptographic software (Sec. 5.1.6)

- Single-factor cryptographic device (Sec. 5.1.7)

- Multi-factor cryptographic software (Sec. 5.1.8)

- Multi-factor cryptographic device (Sec. 5.1.9)

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

Cryptographic authenticators used at AAL1 SHALL use approved cryptography. Software-based authenticators that operate within the context of an operating system MAY, where applicable, attempt to detect compromise (e.g., by malware) of the user endpoint in which they are running and SHOULD NOT complete the operation when such a compromise is detected.

Communication between the claimant and verifier SHALL be via an authenticated protected channel to provide confidentiality of the authenticator output and resistance to adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) attacks.

Verifiers operated by or on behalf of federal government agencies at AAL1 SHALL be validated to meet the requirements of [FIPS140] Level 1.

Reauthentication

Periodic reauthentication of subscriber sessions SHALL be performed as described in Sec. 7.2. At AAL1, reauthentication of the subscriber SHOULD be repeated at least once per 30 days during an extended usage session, regardless of user activity. The session SHOULD be terminated (i.e., logged out) when this time limit is reached.

Security Controls

The CSP SHALL employ appropriately tailored security controls from the baseline security controls defined in [SP800-53] or equivalent federal (e.g., [FEDRAMP]) or industry standard that the organization has determined for the information systems, applications, and online services that these guidelines are used to protect. The CSP SHALL ensure that the minimum assurance-related controls for the appropriate systems, or equivalent, are satisfied.

Records Retention Policy

The CSP SHALL comply with its respective records retention policies in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies, including any National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) records retention schedules that may apply. If the CSP opts to retain records in the absence of any mandatory requirements, the CSP SHALL conduct a risk management process, including assessments of privacy and security risks, to determine how long records should be retained and SHALL inform the subscriber of that retention policy.

Authentication Assurance Level 2

AAL2 provides high confidence that the claimant controls authenticators bound to the subscriber account. Proof of possession and control of two distinct authentication factors is required through secure authentication protocols. Approved cryptographic techniques are required at AAL2 and above.

Permitted Authenticator Types

At AAL2, authentication SHALL occur by the use of either a multi-factor authenticator or a combination of two single-factor authenticators. A multi-factor authenticator requires two factors to execute a single authentication event, such as a cryptographically secure device with an integrated biometric sensor that is required to activate the device. Authenticator requirements are specified in Sec. 5.

When a multi-factor authenticator is used, any of the following MAY be used:

- Multi-Factor Out-of-Band Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.3.4)

- Multi-Factor OTP Device (Sec. 5.1.5)

- Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software (Sec. 5.1.8)

- Multi-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.9)

When a combination of two single-factor authenticators is used, the combination SHALL include a Memorized Secret authenticator (Sec. 5.1.1) and one physical authenticator (i.e., “something you have”) from the following list:

- Look-Up Secret (Sec. 5.1.2)

- Out-of-Band Device (Sec. 5.1.3)

- Single-Factor OTP Device (Sec. 5.1.4)

- Single-Factor Cryptographic Software (Sec. 5.1.6)

- Single-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.7)

Note: When biometric authentication meets the requirements in Sec. 5.2.3, the device has to be authenticated in addition to the biometric match. A biometric characteristic is recognized as a factor, but not recognized as an authenticator by itself. Therefore, when conducting authentication with a biometric characteristic, it is unnecessary to use two authenticators because the associated device serves as “something you have,” while the biometric match serves as “something you are.”

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

Cryptographic authenticators used at AAL2 SHALL use approved cryptography. Authenticators procured by federal government agencies SHALL be validated to meet the requirements of [FIPS140] Level 1. Software-based authenticators that operate within the context of an operating system MAY, where applicable, attempt to detect compromise (e.g., by malware) of the platform in which they are running. They SHOULD NOT complete the operation when such a compromise is detected. At least one authenticator used at AAL2 SHALL be replay resistant as described in Sec. 5.2.8. Authentication at AAL2 SHOULD demonstrate authentication intent from at least one authenticator as discussed in Sec. 5.2.9.

Communication between the claimant and verifier SHALL be via an authenticated protected channel to provide confidentiality of the authenticator output and resistance to AitM attacks.

Verifiers operated by or on behalf of federal government agencies at AAL2 SHALL be validated to meet the requirements of [FIPS140] Level 1.

When a biometric factor is used in authentication at AAL2, the performance requirements stated in Sec. 5.2.3 SHALL be met, and the verifier SHOULD make a determination that the biometric sensor and subsequent processing meet these requirements.

OMB Memorandum [M-22-09] requires federal government agencies to offer at least one phishing-resistant authenticator option to public users at AAL2. While phishing resistance as described in Sec. 5.2.5 is not generally required for authentication at AAL2, verifiers SHOULD encourage the use of phishing-resistant authenticators at AAL2 whenever practical since phishing is a significant threat vector.

Reauthentication

Periodic reauthentication of subscriber sessions SHALL be performed as described in Sec. 7.2. At AAL2, authentication of the subscriber SHALL be repeated at least once per 12 hours during an extended usage session, regardless of user activity. Reauthentication of the subscriber SHALL be repeated following any period of inactivity lasting 30 minutes or longer. The session SHALL be terminated (i.e., logged out) when either of these time limits is reached.

Reauthentication of a session that has not yet reached its time limit MAY require only a memorized secret or a biometric in conjunction with the still-valid session secret. The verifier MAY prompt the user to cause activity just before the inactivity timeout.

Security Controls

The CSP SHALL employ appropriately tailored security controls from the baseline security controls defined in [SP800-53] or equivalent federal (e.g., [FEDRAMP]) or industry standard that the organization has determined for the information systems, applications, and online services that these guidelines are used to protect. The CSP SHALL ensure that the minimum assurance-related controls for the appropriate systems, or equivalent, are satisfied.

Records Retention Policy

The CSP SHALL comply with its respective records retention policies in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies, including any NARA records retention schedules that may apply. If the CSP opts to retain records in the absence of any mandatory requirements, the CSP SHALL conduct a risk management process, including assessments of privacy and security risks to determine how long records should be retained and SHALL inform the subscriber of that retention policy.

Authentication Assurance Level 3

AAL3 provides very high confidence that the claimant controls authenticators bound to the subscriber account. Authentication at AAL3 is based on proof of possession of a key through a cryptographic protocol. AAL3 authentication SHALL use a hardware-based authenticator and an authenticator that provides phishing resistance — the same device MAY fulfill both these requirements. In order to authenticate at AAL3, claimants SHALL prove possession and control of two distinct authentication factors through secure authentication protocols. Approved cryptographic techniques are required.

Permitted Authenticator Types

AAL3 authentication SHALL occur by the use of one of a combination of authenticators satisfying the requirements in Sec. 4.3. Possible combinations are:

- Multi-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.9)

- Single-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.7) used in conjunction with a Memorized Secret (Sec. 5.1.1)

- Multi-Factor OTP device (software or hardware) (Sec. 5.1.5) used in conjunction with a Single-Factor Cryptographic Device (Sec. 5.1.7)

- Multi-Factor OTP device (hardware only) (Sec. 5.1.5) used in conjunction with a Single-Factor Cryptographic Software (Sec. 5.1.6)

- Single-Factor OTP device (hardware only) (Sec. 5.1.4) used in conjunction with a Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.8)

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

Communication between the claimant and verifier SHALL be via an authenticated protected channel to provide confidentiality of the authenticator output and resistance to AitM attacks. At least one cryptographic authenticator used at AAL3 SHALL be phishing resistant as described in Sec. 5.2.5 and SHALL be replay resistant as described in Sec. 5.2.8. All authentication and reauthentication processes at AAL3 SHALL demonstrate authentication intent from at least one authenticator as described in Sec. 5.2.9.

Multi-factor authenticators used at AAL3 SHALL be hardware cryptographic modules validated at [FIPS140] Level 2 or higher overall with at least [FIPS140] Level 3 physical security. Single-factor cryptographic devices used at AAL3 SHALL be validated at [FIPS140] Level 1 or higher overall with at least [FIPS140] Level 3 physical security.

Verifiers at AAL3 SHALL be validated at [FIPS140] Level 1 or higher.

Verifiers at AAL3 SHALL be verifier compromise resistant as described in Sec. 5.2.7 with respect to at least one authentication factor.

Hardware-based authenticators and verifiers at AAL3 SHOULD resist relevant side-channel (e.g., timing and power-consumption analysis) attacks.

When a biometric factor is used in authentication at AAL3, the verifier SHALL make a determination that the biometric sensor and subsequent processing meet the performance requirements stated in Sec. 5.2.3.

Reauthentication

Periodic reauthentication of subscriber sessions SHALL be performed as described in Sec. 7.2. At AAL3, authentication of the subscriber SHALL be repeated at least once per 12 hours during an extended usage session, regardless of user activity, as described in Sec. 7.2. Reauthentication of the subscriber SHALL be repeated following any period of inactivity lasting 15 minutes or longer. Reauthentication SHALL use both authentication factors. The session SHALL be terminated (i.e., logged out) when either of these time limits is reached. The verifier MAY prompt the user to cause activity just before the inactivity timeout.

Security Controls

The CSP SHALL employ appropriately tailored security controls from the baseline security controls defined in [SP800-53] or equivalent federal (e.g., [FEDRAMP]) or industry standard that the organization has determined for the information systems, applications, and online services that these guidelines are used to protect. The CSP SHALL ensure that the minimum assurance-related controls for the appropriate systems, or equivalent, are satisfied.

Records Retention Policy

The CSP SHALL comply with its respective records retention policies in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies, including any NARA records retention schedules that may apply. If the CSP opts to retain records in the absence of any mandatory requirements, the CSP SHALL conduct a risk management process, including assessments of privacy and security risks, to determine how long records should be retained and SHALL inform the subscriber of that retention policy.

Privacy Requirements

The CSP SHALL employ appropriately tailored privacy controls defined in [SP800-53] or equivalent industry standard.

If CSPs process attributes for purposes other than identity proofing, authentication, or attribute assertions (collectively “identity service”), related fraud mitigation, or to comply with law or legal process, CSPs SHALL implement measures to maintain predictability and manageability commensurate with the privacy risk arising from the additional processing. Measures MAY include providing clear notice, obtaining subscriber consent, or enabling selective use or disclosure of attributes. When CSPs use consent measures, CSPs SHALL NOT make consent for the additional processing a condition of the identity service.

Regardless of whether the CSP is an agency or private sector provider, the following requirements apply to a federal agency offering or using the authentication service:

- The agency SHALL consult with their Senior Agency Official for Privacy (SAOP) and conduct an analysis to determine whether the collection of PII to issue or maintain authenticators triggers the requirements of the Privacy Act of 1974 [PrivacyAct] (see Sec. 9.4).

- The agency SHALL publish a System of Records Notice (SORN) to cover such collections, as applicable.

- The agency SHALL consult with their SAOP and conduct an analysis to determine whether the collection of PII to issue or maintain authenticators triggers the requirements of the E-Government Act of 2002 [E-Gov].

- The agency SHALL publish a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) to cover such collection, as applicable.

Summary of Requirements

Table 1 provides a non-normative summary of the requirements for each of the AALs.

Table 1 AAL Summary of Requirements

| Requirement | AAL1 | AAL2 | AAL3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permitted authenticator types | Memorized Secret; Look-up Secret; Out-of-Band; SF OTP Device; MF OTP Device; SF Crypto Software; SF Crypto Device; MF Crypto Software; MF Crypto Device | MF Out-of-Band; MF OTP Device; MF Crypto Software; MF Crypto Device; or Memorized Secret plus: Look-up Secret, Out-of-Band, SF OTP Device, SF Crypto Software, SF Crypto Device | MF Crypto Device; SF Crypto Device plus Memorized Secret; SF OTP Device plus MF Crypto Device or Software; SF OTP Device plus SF Crypto Software plus Memorized Secret |

| FIPS 140 validation | Level 1 (Government agency verifiers) | Level 1 (Government agency authenticators and verifiers) | Level 2 overall (MF authenticators) Level 1 overall (verifiers and SF Crypto Devices) Level 3 physical security (all authenticators) |

| Reauthentication | 30 days | 12 hours or 30 minutes inactivity; one authentication factor | 12 hours or 15 minutes inactivity; both authentication factors |

| Security controls | [SP800-53] Low Baseline (or equivalent) | [SP800-53] Moderate Baseline (or equivalent) | [SP800-53] High Baseline (or equivalent) |

| AitM resistance | Required | Required | Required |

| Phishing resistance | Not required | Recommended | Required |

| Verifier-compromise resistance | Not required | Not required | Required |

| Replay resistance | Not required | Required | Required |

| Authentication intent | Not required | Recommended | Required |

Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

This section is normative.

このセクションでは, 各 Authenticator タイプ固有の詳細な要件を提供する. Sec. 4で指定された Reauthentication の要件および Sec. 5.2.5 で説明された AAL3 での Phishing 耐性のための要件を除いて, Authenticator が使用される AAL に関係なく, 各 Authenticator タイプの技術要件は同じである.

Requirements by Authenticator Type

Memorized Secrets

Memorized Secret Authenticator — 一般に Password または数値の場合は PIN と言われる — は, ユーザーによって選択され記憶されることを意図した秘密の値である. Memorized Secret は, Attacker が正しい Secret Value を推測または発見することが現実的でないように, 十分に複雑で秘匿されている必要がある. Memorized Secret は something you know である.

このセクションの要件は, Authenticated Protected Channel を介して CSP の Verifier に送信される, 独立した Authentication Factor として使用される中央で検証された Memorized Secret に適用される. Multi-Factor Authenticator によってローカルで使用される Memorized Secret は, Activation Secret と呼ばれ, Sec. 5.2.11 で議論される.

Memorized Secret Authenticators

Memorized Secret は, 長さが少なくとも8文字となる(SHALL). Memorized Secret は, Subscriber によって選択されるか, CSP によってランダムに割り当てられることとなる(SHALL).

CSP が, 頻繁に使用される, 予期される, または侵害されている値の Blocklist にあるために, 選択された Memorized Secret を許可しない場合 (Sec. 5.1.1.2 を参照), Subscriber は別の Memorized Secret を選択することになる(SHALL). Memorized Secret に他の複雑さの要件が課されることはない(SHALL). この根拠は, Appendix A Strength of Memorized Secrets に示される.

Memorized Secret Verifiers

Verifier は, 長さが少なくとも8文字の Memorized Secret を要求することとする(SHALL). Verifier は, Memorized Secret の長さが少なくとも64文字であることを許可する必要がある(SHOULD). すべての Printing ASCII 文字 [RFC20] と空白文字は Memorized Secret に受け入れられる必要がある(SHOULD). Unicode 文字 [ISO/ISC 10646] も同様に受け入れられる必要がある(SHOULD). Verifier は, Verification の前に先頭と末尾の空白文字を削除したり, 先頭の文字の大文字と小文字が異なる Memorized Secret の Verification を許可したり, 残りの文字数が8文字以上ある場合に先頭の文字の大文字・小文字が異なっていることを許したりなど, タイプミスの可能性を許容してもよい(MAY).

Verifier は, 提出された Memorized Secret 全体を検証することになる(SHALL)(つまり, Secret を切り詰めない). 前述の長さの要件に関して, 各 Unicode コードポイントは1文字としてカウントされることになる(SHALL).

Memorized Secret でUnicode文字が受け入れられる場合, Verifier は Sec. 12.1 of Unicode Normalization Forms [UAX15] で定義された NFKC または NFKD 正規化を使用して, スタビライズされた文字列の正規化プロセスを適用する必要がある(SHOULD). このプロセスは, Memorized Secret を表すバイト文字列をHash する前に適用される. Unicode 文字を含む Memorized Secret を選択する Subscriber は, 一部の文字が一部のエンドポイントによって異なる方法で表現される可能性があることを通知される必要がある(SHOULD). これは, 正常に Authenticate する能力に影響を与える可能性がある.

Memorized Secret の Verifier は, Subscriber に対して, Authenticate されていない Claimant がアクセスできるヒントを保存することを許可することはない(SHALL NOT). Verifier は, Memorized Secret を選択する際に, Subscriber に特定の種類の情報 (例えば, 「あなたの最初のペットの名前は何ですか?」といった Knowledge-Based Authentication (KBA) または秘密の質問として知られる手法) を使用するように促すことはない(SHALL NOT).

Memorized Secret を確立および変更するリクエストを処理するとき, Verifier は, 頻繁に使用される, 予期される, または侵害されていることが知られている値を含む Blocklist と, リクエストされた Secret を比較することになる(SHALL). 例えば, リストには以下を含んでもよい(MAY) が, これらに限定されない:

- 以前の侵害事例から得られた Password.

- 辞書の単語.

- 反復または連続した文字 (例: ‘aaaaaa’, ‘1234abcd’).

- サービスの名前, ユーザー名, およびその派生語など, コンテキスト特有の単語.

選択された Secret が Blocklist の中にある場合, CSP または Verifier は Subscriber に別の Secret を選択する必要があることを通知することとなり(SHALL), 拒否の理由を提供することになり(SHALL), Subscriber に別の値を選択することを要求することになる(SHALL). Blocklist はブルートフォース Attack を防御するために使用され, 試行の失敗は以下で説明するようにレート制限されるため, Blocklist は Subscriber が Attacker が試行リミットに到達する前に推測する可能性のある Memorized Secret を選択することを防ぐのに十分なサイズにする必要がある(SHOULD). 過度に大きな Blocklist は使用しないほうがよい(SHOULD NOT). これは, Subscriber が許容される Memorized Secret を確立しようとする試みを妨げ, 大幅に改善されたセキュリティを提供しないためである.

Verifierは, 強力な Memorized Secret を選択する際にユーザーを支援するために, Subscriber にガイダンスを提供することとなる(SHALL). これは, リストされた (そしておそらく非常に弱い) Memorized Secret への浅はかな変更を思いとどまらせるため, 上記のリストにある Memorized Secret の拒否に続いて特に重要である. [Blocklists]

Verifier は, Sec. 5.2.2 で説明されている通り, Subscriber Account で試行できる Authentication の失敗回数を効果的に制限するレート制限メカニズムを実装することとなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, Memorized Secret に他の構成ルールを課すことはない(SHALL NOT) (例: 異なる文字タイプの混合の要求, 連続して繰り返される文字の禁止). Verifier は, Memorized Secret を定期的に変更することをユーザーに要求することはない(SHALL NOT). ただし, Authenticator の侵害の証拠がある場合, Verifier は変更を強制することとなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, Passwordマネージャーの使用を許可することになる(SHALL). それらを使用しやすくするために, Verifier は, Memorized Secret を入力するときに, Claimant が「貼り付け」機能の使用を許可ことになる(SHALL). Passwordマネージャーは, ユーザーがより強力な Memorized Secret を選択する可能性を高める場合がある.

Claimant が Memorized Secret を正常に入力することを支援するために, Verifier は, 入力されている間および Verifier に送信されるまで, 一連のドットやアスタリスクではなく, Secret を表示するオプションを提供する必要がある(SHOULD). これにより Claimant は, 自分の画面が観察される可能性が低い場所にいる場合, 自分の入力を確認できる. Verifier は, 各文字が入力された後, 正しく入力したかを確認するために入力された個々の文字を短時間表示することを Claimant のデバイスに許可してもよい(MAY). これは, モバイルデバイスでは一般的である.

Verifier は, Memorized Secret を要求するときには, 盗聴や Adversary-in-the-Middle Attack に対する耐性を提供するために, Approved な暗号による暗号化と Authenticated Protected Channel を使用することになる(SHALL).

Verifier は, Memorized Secret を Offline Attack に耐性のある形式で保存することになる(SHALL). Memorized Secret は, 適切な Password Hash スキームを使用して Salt および Hash されることになる(SHALL). Password Hash スキームは, Password, Salt, およびコストファクターを入力として受け取り, Password Hash を生成する. それらの目的は, Hash された Password ファイルを取得した Attacker に対して, 各 Password の推測をより高価なものにし, それによって推測攻撃のコストを高くしたり法外なものにしたりすることである. Attack のコストを増加させるため, Memory-Hard と Compute-Hard の両方の性質を持つ関数を使用する必要がある(SHOULD). NIST は特定の Password Hash スキームに関するガイドラインを公開していないが, そのような関数の例には Argon2 [Argon2] や scrypt [Scrypt] などがある. Approved な一方向関数の例には, Keyed Hash Message Authentication Code (HMAC) [FIPS198-1], [SP800-107] で Approved ないずれかの Hash 関数, Secure Hash Algorithm 3 (SHA-3) [FIPS202], CMAC [SP800-38B], Keccak Message Authentication Code (KMAC), Customizable SHAKE (cSHAKE), および ParallelHash [SP800-185] が含まれる. Password Hash スキームが処理した出力の長さは, 基になる一方向関数の出力の長さと同じである必要がある(SHOULD).

Salt は長さが少なくとも 32 ビットとなり, 保存された Hash 間の Salt 値の衝突を最小限に抑えるためにばらついて選択されることとなる(SHALL). Salt 値と結果の Hash の両方が, Memorized Secret Authenticator ごとに保存されることとなる(SHALL).

Password-based Key Derivation Function 2 (PBKDF2) [SP800-132] の場合, コストファクターは反復回数である. PBKDF2 関数が反復される回数が多いほど, Password Hash の計算に時間がかかる. したがって, 反復回数は, Verification サーバのパフォーマンスが許す限り大きくする必要がある(通常, 少なくとも10,000回の反復)(SHOULD).

さらに, Verifier は, Verifier のみが知っている Secret Key を使用して, 鍵付き Hash または暗号化オペレーションの追加の反復を実行する必要がある(SHOULD). この Key 値を使用する場合, Approved Random Bit Generator [SP800-90Ar1] によって生成され, 少なくとも NIST SP 800-131A Transitioning the Use of Cryptographic Algorithms and Key Lengths [SP800-131A] の最新リビジョンで指定されている最小のセキュリティ強度を提供することとなる(この発行日時点で112ビット)(SHALL). Secret Key の値は, Hash された Memorized Secret とは別に保存されることとなる(例えば, Hardware Security Moduleのような特別なデバイスに)(SHALL). この追加の反復により, Secret Key の値が秘密のままである限り, Hash された Memorized Secret に対するブルートフォース Attack は非現実的である.

Look-Up Secrets

Look-up Secret Authenticator は, Claimant と CSP の間で共有される一連の Secret を格納する物理的または電子的な記録である. Claimant は, Verifier からのプロンプトに応答するために必要な, 適切な Secret を見つけるために Authenticator を使用する. 例えば, Verifier は, 表形式でカードに印刷された数値または文字列の特定のサブセットを提供するように Claimant に尋ねることができる. Look-up Secret の一般的な用途は, 別の Authenticator が紛失されたり故障した場合に使用するために, Subscriber によって保管された1回限りの”回復キー”としての使用である. Look-up Secret は something you have である.

Look-Up Secret Authenticators

Look-up Secret Authenticator を作成する CSP は, Approved Random Bit Generator [SP800-90Ar1] を使用して Secret のリストを生成することとなり(SHALL), Authenticator を Subscriber に安全に配布することとなる(SHALL). Look-up Secret は, 少なくとも20ビットの Entropy を持つこととなる(SHALL).

Look-up Secret Authenticator は, CSP が対面で, Subscriber の Address of Record へ郵便で, またはオンラインで配布してもよい(MAY). オンラインで配布される場合, Look-up Secret は Sec. 6.1.2 にある Post-Enrollment Binding の要件に従って, セキュアなチャネルを介して配布されることとなる(SHALL).

Authenticator がリストからシーケンシャルに Look-up Secret を使用する場合, Authentication が成功した後に限り, Subscriber は使用済みの Secret を破棄してもよい(MAY).

Look-Up Secret Verifiers

Look-up Secret の Verifier は, Claimant に, 彼らの Authenticator からの次の Secret, または特定の (例えば, 番号が振られた) Secret を要求することとなる(SHALL). Authenticator から与えられた Secret は, 一度だけ成功として使用されることとなる(SHALL). Look-up Secret がグリッド カードから得られたものである場合, グリッドの各セルは一度だけ使用されることとなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, Offline Attack に耐性のある形式で Look-up Secret を保存することとなる(SHALL). 少なくとも 112 ビットの Entropy を持つ Look-up Secret は, Sec. 5.1.1.2 で述べられた通り, Approved な一方向関数で Hash されることとなる(SHALL). Entropy が 112 ビット未満の Look-up Secret は, 同様にSec. 5.1.1.2で述べられた通り, Salt 化され適切な Password Hash スキームを使用して Hash されることとなる(SHALL). Salt 値は長さが少なくとも 32 ビット となり, 保存された Hash 間の Salt 値の衝突を最小限に抑えるためにばらついて選択されることとなる(SHALL). Salt 値と結果の Hash の両方が, Look-up Secret ごとに保存されることとなる(SHALL).

Entropy が 64 ビット未満の Look-up Secret の場合, Verifier は, Sec. 5.2.2 で説明されている通り, Subscriber Account で試行できる Authentication の失敗回数を効果的に制限するレート制限メカニズムを実装することとなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, Look-up Secret を要求するときには, 盗聴や AitM Attack に対する耐性を提供するために, Approved な暗号による暗号化と Authenticated Protected Channel を使用することになる(SHALL).

Out-of-Band Devices

Out-of-band Authenticator は, 一意にアドレス指定が可能で, セカンダリチャネルと呼ばれる個別の通信チャネルを介して Verifier と安全に通信できる物理デバイスである. デバイスは Claimant によって所有および制御され, Authentication のためのプライマリチャネルとは別に, このセカンダリチャネルを介したプライベート通信をサポートする. Out-of-band Authenticator は something you have である.

Out-of-band Athentiction は, Verifier によって生成された短期的な Secret を使用する. Secret の目的は, プライマリとセカンダリチャネルでの Athentiction 操作を安全にバインドし, Claimant による Out-of-band デバイスの制御を確立することである.

Out-of-band Authenticator は以下のいずれかの方法で動作できる:

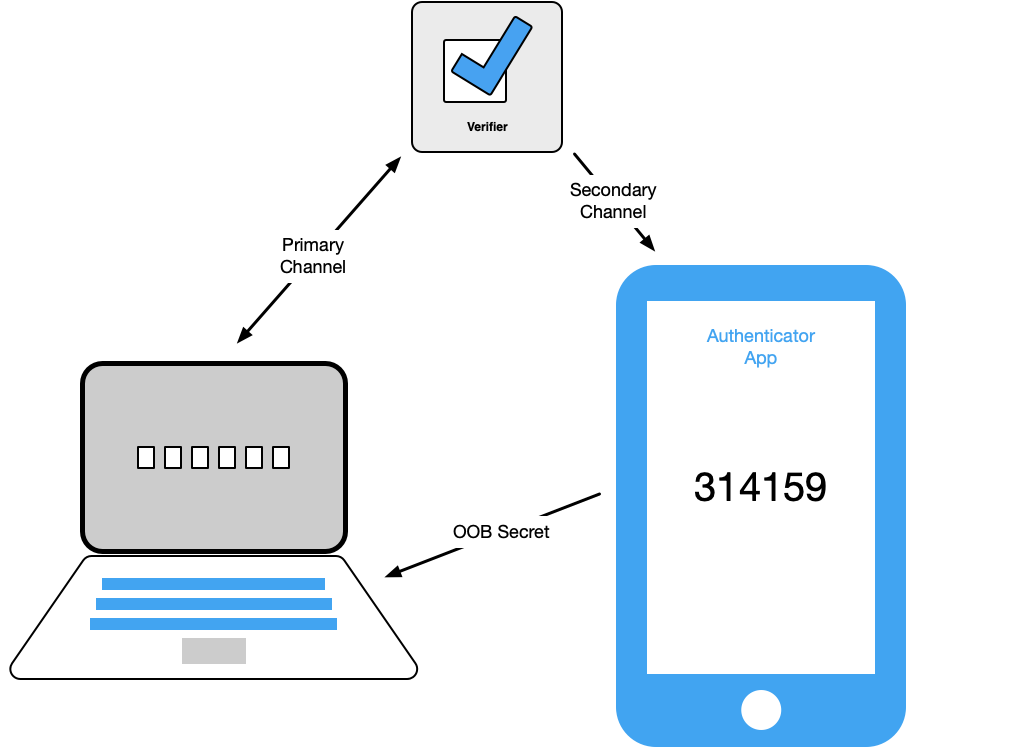

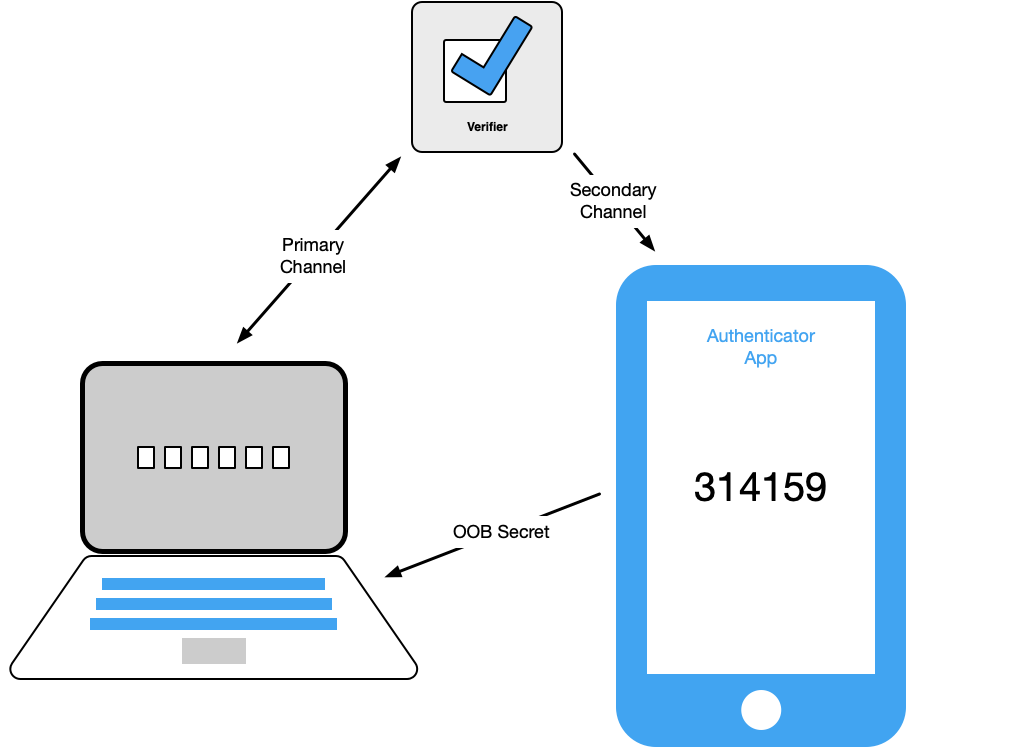

- Claimant は, Out-of-band デバイスによってセカンダリチャネルを介して受信した Secret を, プライマリチャネルを使用して Verifier に転送する. 例えば, Claimant はモバイルデバイスで Secret (通常は6桁のコード) を受信し, それを Authentication Session に入力してもよい. この方法は Figure 1 に示される.

Figure 1. Transfer of Secret to Primary Device

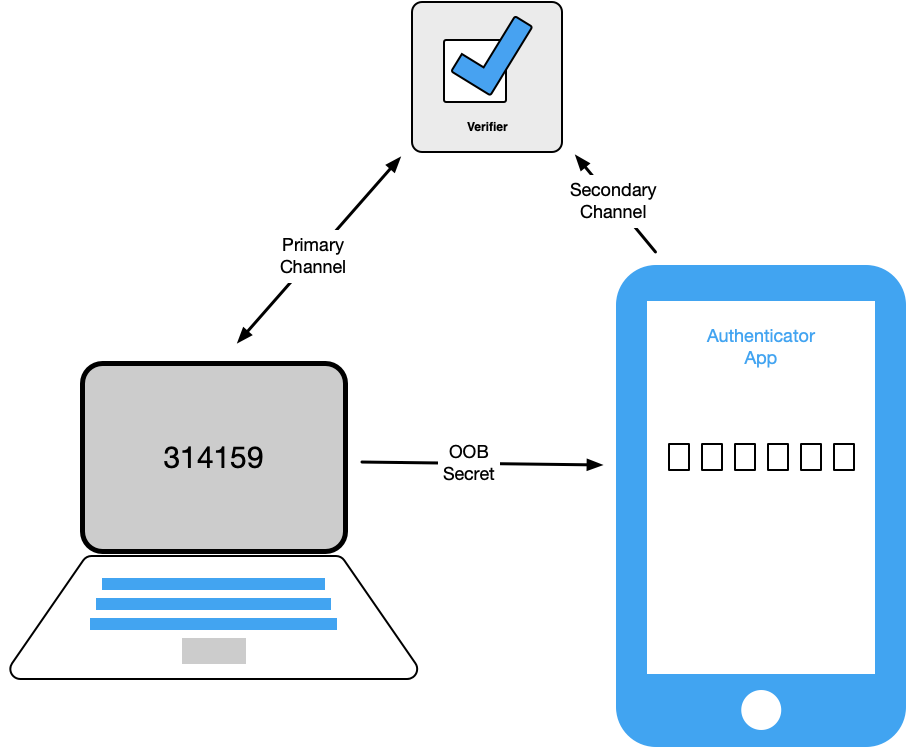

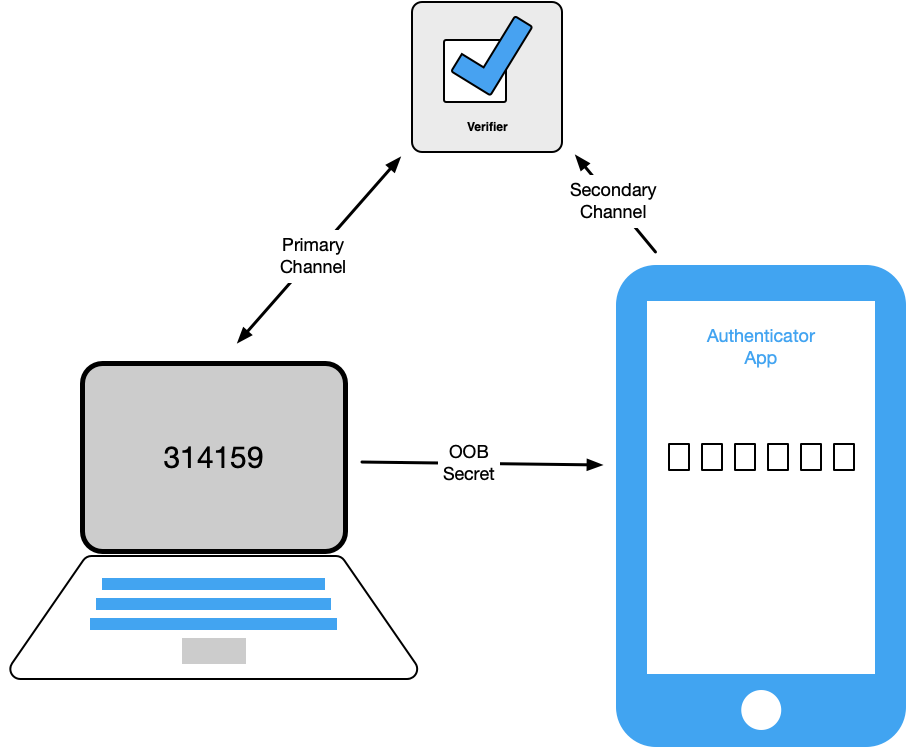

- Claimant は, セカンダリチャネルを介して Verifier に送信するために, プライマリチャネルを介して受信した Secret を Out-of-band デバイスに転送する. 例えば, Claimant は Authentication Session 上で Secret を表示し, モバイルデバイスのアプリにそれを入力するか, バーコードやQRコードなどのテクノロジーを使用して転送を行ってもよい. この方法は Figure 2 に示される.

Figure 2. Transfer of Secret to Out-of-band Device

注: 三番目の方法であった, プライマリとセカンダリチャネルから受信した Secret の比較とセカンダリチャネルでの承認による Out-of-band Authentication は, 説明された通りに実装されることは稀であったため, もはや受け入れられないと見なされる. これは Claimant が Secret を実際に比較せず単に承認する可能性を高くしていた. 例えば, Verifier からプッシュ通知を受け取り, 単に Claimant に Transaction の承認を求めるだけの Authenticator は (たとえ Authentication に関する追加情報を提供したとしても), このセクションの要件を満たさない.

Out-of-Band Authenticators

Out-of-band Authenticator は, Out-of-band Secret または Authentication 要求を取得するために, Verifier と別のチャネルを確立することとなる(SHALL). このチャネルは, デバイスが Claimant の許可なしにひとつのチャネルから別のチャネルに情報を漏らさないという条件であれば, (たとえ同じデバイス上で完了する場合でも) プライマリ通信チャネルに関して Out-of-band であると見なされる.

Out-of-band デバイスは, Verifier によって一意にアドレス指定が可能である必要がある(SHOULD). セカンダリチャネルを介した通信は, 公衆交換電話網 (Public Switched Telephone Network, PSTN) 経由で送信されない限り, 暗号化されることとなる(SHALL). Out-of-band Authentication のために PSTN を使用する場合の追加の Authenticator 要件については, Sec. 5.1.3.3 を参照のこと. Voice-Over-IP (VOIP) 電話番号など, 特定のデバイスの所有を証明しないチャネルまたはアドレスは, Out-of-band Authentication に使用されることはない(SHALL NOT).

電子メールは特定のデバイスの所有を証明するものではなく, 通常は Memorized Secret のみを使用してアクセスされるため, Out-of-band Authentication に使用されることはない(SHALL NOT).

Out-of-band Authenticator は, Verifier と通信するときに, 以下のいずれかの方法で自身を一意に Authentication することとなる(SHALL).

- Approved Cryptography を使用して, Verifier への Authenticated Protected Channel を確立する. 使用されるキーは, Authenticator アプリケーションが利用可能な, 適切に安全なストレージ (例: キーチェーンストレージ, TPM, TEE, セキュアエレメントなど) に格納することとなる(SHALL).

- デバイスを一意に識別する SIM カードまたは同等のものを使用して, 公衆携帯電話ネットワークに対して Authentication する. このメソッドは, Secret が Verifier から PSTN (SMS または音声) 経由で Out-of-band デバイスに送信される場合にのみ使用されることとなる(SHALL).

Verifier によって Out-of-band デバイスに Secret が送信される場合, デバイスは, 所有者によってロックされている間, Authentication Secret を表示しないほうがよい(SHOULD NOT)(つまり, 表示のために PIN, パスコード, または Biometric Characteristic の提示と Verification を要求する必要がある(SHOULD). ただし, Authenticator は, ロックされたデバイス上で Authentication Secret の受信を示す必要がある(SHOULD).

Out-of-band Authenticator が, (Claimant がプライマリ通信チャネルに転送する Secret を提示するのではなく) セカンダリ通信チャネルで承認を要求する場合, プライマリチャネルからの Secret の転送を受け入れることとなり(SHALL), 承認を Authentication Transaction に関連付けるために, それをセカンダリチャネルを介して Verifier に送信することとなる. Claimant は, 転送を手動で行うか, バーコードやQRコードなどのテクノロジーを使用して転送を行ってもよい(MAY).

Out-of-Band Verifiers

PSTN に固有の追加の Verification 要件については, Sec. 5.1.3.3 を参照のこと.

Out-of-band Authenticator がスマートフォン上などの安全なアプリケーションである場合, Verifier はそのデバイスにプッシュ通知を送信してもよい(MAY). Verifier は, Out-of-band Authenticator との Authenticated Protected Channel の確立を待ち, その識別キーを Verifiy する. Verifier は識別キー自体を保管することはない(SHALL NOT)が, Verification 方法 (例えば, Approved なハッシュ関数または識別キーの所有の証明) を使用して, Authenticator を一意に識別することとなる(SHALL). ひとたび Authenticate されると, Verifier は Authentication Secret を Authenticator に送信する.

Out-of-band Authenticator のタイプに応じて, 以下のいずれかが行われることとなる(SHALL):

- セカンダリからプライマリチャネルへの Secret の転送: Verifier は, Authentication の準備ができていることを示すために, Subscriber の Authenticator を含むデバイスにシグナルを送ってもよい(MAY). そして, Random Secret を Out-of-band Authenticator に送信することとなる(SHALL). 続いて, Verifier は, プライマリ通信チャネル上で Secret が返却されるのを待つこととなる(SHALL).

- プライマリからセカンダリチャネルへの Secret の転送: Verifier は, プライマリチャネルを介して Claimant に Random Authentication Secret を表示することとなる(SHALL). そして, Claimant の Out-of-band Authenticator からセカンダリチャネル上で Secret が返却されるのを待つこととなる(SHALL).

すべてのケースで, 10分以内に完了しない場合, Authentication は無効と見なされることとなる(SHALL). Sec. 5.2.8で述べられた通りに Replay Resistance を提供するため, Verifier は, 与えられた Authentication Secret の受け入れを有効期間中に一度のみとすることとなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, Approved Random Bit Generator [SP800-90Ar1] を使用して, 少なくとも 20 ビットの Entropy を持つ Random Authentication Secret を生成することとなる(SHALL). Authentication Secret の Entropy が 64 ビット未満の場合, Verifier は, Sec. 5.2.2 で説明されている通り, Subscriber Account で試行できる Authentication の失敗回数を効果的に制限するレート制限メカニズムを実装することとなる(SHALL).

CSP が, Out-of-band Authentication が Sec. 5.1.3.4 の要件を満たしていることを確認しない限り, Out-of-band Verifier はすべての Authentication 操作を Single-Factor と見なすこととなる(SHALL). この要件は CSP または信頼されたサードパーティによる Authenticator の発行, またはこれらの要件を満たすことが CSP によって認識されている Authentication アプリケーションの使用によって満たされてもよい(MAY).

Subscriber のデバイスにプッシュ通知を送信する Out-of-band Verifier は, 成功した最後の Authentication 以降に送信されるプッシュ通知のレートまたは総数に合理的な制限を実装する必要がある(SHOULD).

Authentication using the Public Switched Telephone Network

Out-of-band Verification のための PSTN の使用は, このセクションと Sec. 5.2.10 で説明されているように制限されている. PSTN を使用して Out-of-band Verification を行う場合, Verifier は, 使用されている事前登録済みの電話番号が特定の物理デバイスに関連付けられていることを Verification することとなる(SHALL). 事前登録された電話番号の変更は, 新しい Authenticator のバインドであると見なされ, Sec. 6.1.2 で説明されている場合にのみ発生することとなる(SHALL).

PSTN を使用して Out-of-band Authentication Secret を配信することは, 限定された電話のカバレッジを持つ地域 (特に携帯電話サービスがない地域) では, 一部の Subscriber が利用できない可能性がある. したがって, Verifier は, すべての Subscriber が代替の Authenticator タイプを利用できるようにすることとなり(SHALL), バインドする前に, PSTN を使用した Out-of-band Authenticator のこの制限を Subscriber に通知する必要がある(SHOULD).

Verifier は, PSTN を使用して Out-of-band Authentication Secret を配信する前に, デバイスの交換, SIM の変更, 番号の移植, またはその他の異常な動作などのリスク指標を考慮する必要がある(SHOULD).

注意: Sec. 5.2.10 の Authenticator の制限と整合性を取り, NIST は, 脅威をとりまく状況の進化と PSTN の技術的なオペレーションに基づいて, 時間の経過とともに, PSTN の制限付きステータスを調整してもよい.

Multi-Factor Out-of-Band Authenticators

Multi-Factor Out-of-band Authenticator は, Claimant が Authentication Transaction を完了できるようにする前(つまり, Authentication Secret にアクセスする前, Authentication Secret を入力する前, または使用されている Authentication フローに適した Transaction を確認する前)に Memorized Secret または Biometric Characteristic のいずれかの追加要素の提示と Verification を必要とすることを除いて, Single-Factor Out-of-band Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.3.1を参照) と同様の方法で動作する. Authenticator の使用ごとに, Activation Factor の提示を要求することとなる(SHALL).

Authenticator による Activation Secret の使用は, Sec. 5.2.11 の要件を満たすこととなる(SHALL). Biometric Activation Factor は, Authentication の連続失敗回数の制限を含め, Sec. 5.2.3 の要件を満たすこととなる(SHALL). Activation Factor の提出は, ホストデバイス (スマートフォンなど) のロック解除とは別の操作となる(SHALL)が, ホストデバイスのロック解除に使用されたものと同じ Activation Factor が Authentication 操作で使用されてもよい(MAY). Activation に使用される Memorized Secret または Biometric Sample -および信号処理によって生成された Probe などの Biometric Sample から得られたすべての Biometric データ- は, Authentication 操作の直後に Zeroize されることとなる(SHALL).

Single-Factor OTP Device

Single-Factor OTP デバイスは, ワンタイムパスワード(OTP)を生成する. このカテゴリには, ハードウェアデバイスと携帯電話などのデバイス上にインストールされた Software-Based OTP Generator が含まれる. これらのデバイスは, OTP 生成のシードとして使用される組み込みの Secret を持ち, 二番目の要素による Activation を必要としない. OTP はデバイス上に表示され Verifier に送信するために手動で入力される, これによりデバイスの所有と制御が証明される. OTP デバイスは, 例えば, 一度に6文字を表示してもよい. Single-Factor OTP デバイスは something you have である.

Single-Factor OTP デバイスは, Secret が Authenticator と Verifier によって暗号論的にかつ独立して生成され, Verifier によって比較されることを除いて, Look-up Secret Authenticator と同様である. Secret は, 時間ベースの Nonce に基づいて, または Authenticator と Verifier の数値カウンターから計算されてもよい.

Single-Factor OTP Authenticators

Single-Factor OTP Authenticator は, 2つの永続的な値を含む. 1つ目は, デバイスのライフタイムの間保持される Symmetric Key である. 2つ目は, Authenticator が使用されるたびに変更されるか, リアルタイムクロックに基づく Nonce である.

Secret Key とそのアルゴリズムは, 少なくとも [SP800-131A] の最新リビジョンで指定されている最小のセキュリティ強度を提供することとなる(SHALL)(発行日現在で 112 ビット). Nonce は, デバイスのライフタイム全体にわたってデバイスの各操作ごとに一意であることを確保するのに十分な長さとなる(SHALL). Subscriber が Software-Based OTP Authenticator に使用されるデバイスを変更する必要がある場合, 彼らは Sec. 6.1.2.1 で説明されている通りに新しいデバイス上の Authenticator を Subscriber Account へバインドする必要があり(SHOULD), 使用されなくなった Authenticator アプリケーションを無効にする必要がある.

Authenticator Output は, Key と Nonce を安全な方法で結合するために Approved なブロック暗号または Hash 関数を使用すること取得される. Authenticator Output は, わずか6桁の10進数 (約20ビットのEntropy) に切り詰められられてもよい(MAY).

Authenticator Output を生成するために使用される Nonce がリアルタイムクロックに基づいている場合, Nonce は少なくとも2分ごとに変更されることとなる(SHALL).

Single-Factor OTP Verifiers

Single-Factor OTP Verifier は, Authenticator に使用される OTP 生成プロセスを効果的に複製する. そのため, Authenticator に使用される Symmetric Key は Verifier にもまた存在し, アクセスを必要とするデバイス上のそれらのソフトウェアコンポーネントのみに Key へのアクセスを制限するアクセスコントロールを使用して, 無許可の開示から強力に保護されることとなる(SHALL).

Single-Factor OTP Authenticator が Subscriber Account に関連付けられている場合, Verifier または関連付けられた CSP は, Authenticator Output を複製するために必要な Secret を生成および交換, または取得するために, Approved Cryptography を使用することとなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, OTP を収集するときに, 盗聴や AitM Attack への耐性を提供するために, Approved Encryption と Authenticated Protected Channel を使用することとなる(SHALL). Sec. 5.2.8 で説明されている通りに Replay Resistance を提供するために, Verifier は, 有効な OTP の受け入れを一度のみとすることとなる(SHALL). OTP の重複使用が原因で Claimant の Authentication が拒否された場合, Verifier は, Attacker が事前に Authenticate できた場合に備えて Claimant に警告してもよい(MAY). また, Verifier は, OTP の重複使用の試行について, 既存セッションの中にいる Subscriber に警告してもよい(MAY).

時間ベースの OTP [TOTP] は, ネットワーク遅延と OTP のユーザー入力のための許容値, それに加え Authenticator が寿命の間に持つはずの両方向のクロックのずれを考慮した上で決定される, 定義されたライフタイムを持つこととなる(SHALL).

Authenticator Output の Entropy が 64 ビット未満の場合, Verifier は, Sec. 5.2.2 で説明されている通り, Subscriber Account で試行できる Authentication の失敗回数を効果的に制限するレート制限メカニズムを実装することとなる(SHALL).

Multi-Factor OTP Devices

Multi-Factor OTP デバイスは, Activation Factor の入力による Activation 後に Authentication に使用する OTP を生成する. これには, ハードウェアデバイスと携帯電話などのデバイス上にインストールされた Software-Based OTP Generator が含まれる. Authentication の二番目の要素は, 一体型入力パッドのようなもの, 一体型Biometric (例: 指紋) リーダー, または直接的なコンピュータインターフェース (例: USB ポート) によって実現されてもよい. OTP はデバイス上に表示され Verifier に送信するために手動で入力される. 例えば, OTP デバイスは一度に6文字を表示することができ, それによってデバイスの所有と制御を証明する. Multi-Factor OTP デバイスは something you have であり, かつ, something you know または something you are のいずれかによって Activation されることとなる(SHALL).

Multi-Factor OTP Authenticators

Multi-Factor OTP Authenticator は, Authenticator から OTP を取得するために Memorized Secret または Biometric Characteristic のいずれかの提示と Verification を必要とすることを除いて, Single-Factor OTP Authenticator (Sec. 5.1.4.1を参照) と同様の方法で動作する. Authenticator の使用ごとに, Activation Factor の入力を要求することとなる(SHALL).

Activation 情報に加えて, Multi-Factor OTP Authenticator は, 2つの永続的な値を含む. 1つ目は, デバイスのライフタイムの間保持される Symmetric Key である. 2つ目は, Authenticator が使用されるたびに変更されるか, リアルタイムクロックに基づく Nonce である.

Secret Key とそのアルゴリズムは, 少なくとも [SP800-131A] の最新リビジョンで指定されている最小のセキュリティ強度を提供することとなる(SHALL)(発行日現在で 112 ビット). Nonce は, デバイスのライフタイム全体にわたってデバイスの各操作ごとに一意であることを確保するのに十分な長さとなる(SHALL). Subscriber が Software-Based OTP Authenticator に使用されるデバイスを変更する必要がある場合, 彼らは Sec. 6.1.2.1 で説明されている通りに新しいデバイス上の Authenticator を Subscriber Account へバインドする必要があり(SHOULD), 使用されなくなった Authenticator アプリケーションを無効にする必要がある.

Authenticator Output は, Key と Nonce を安全な方法で結合するために Approved なブロック暗号または Hash 関数を使用すること取得される. Authenticator Output は, わずか6桁の10進数 (約20ビットのEntropy) に切り詰められられてもよい(MAY).

Authenticator Output を生成するために使用される Nonce がリアルタイムクロックに基づいている場合, Nonce は少なくとも2分ごとに変更されることとなる(SHALL).

Authenticator による Activation Secret の使用は, Sec. 5.2.11 の要件を満たすこととなる(SHALL). Biometric Activation Factor は, Authentication の連続失敗回数の制限を含め, Sec. 5.2.3 の要件を満たすこととなる(SHALL). Activation Factor の提出は, ホストデバイス (スマートフォンなど) のロック解除とは別の操作となる(SHALL)が, ホストデバイスのロック解除に使用されたものと同じ Activation Factor が Authentication 操作で使用されてもよい(MAY). Unencrypted Key と Activation Secret, または Biometric Sample -および信号処理によって生成された Probe などの Biometric Sample から得られたすべての Biometric データ- は, Authentication 操作の直後に Zeroize されることとなる(SHALL).

Multi-Factor OTP Verifiers

Multi-Factor OTP Verifier は, 二番目の要素を提供を受ける要件なしに Authenticator に使用される OTP 生成プロセスを効果的に複製する. そして, Authenticator に使用される Symmetric Key はアクセスを必要とするデバイス上のそれらのソフトウェアコンポーネントのみに Key へのアクセスを制限するアクセスコントロールを使用して, 無許可の開示から強力に保護されることとなる(SHALL).

Multi-Factor OTP Authenticator が Subscriber Account に関連付けられている場合, Verifier または関連付けられた CSP は, Authenticator Output を複製するために必要な Secret を生成および交換, または取得するために, Approved Cryptography を使用することとなる(SHALL). Verifier または CSP は, Authenticator の発行によって, Authenticator が Multi-Factor デバイスであることを確立することとなる(SHALL). それ以外の場合, Verifier は, Sec. 5.1.4 に従って, Authenticator を Single-Factor として扱うこととなる(SHALL).

Verifier は, OTP を収集するときに, 盗聴や AitM Attack への耐性を提供するために, Approved Encryption と Authenticated Protected Channel を使用することとなる(SHALL). Sec. 5.2.8 で説明されている通りに Replay Resistance を提供するために, Verifier は, 有効な OTP の受け入れを一度のみとすることとなる(SHALL). OTP の重複使用が原因で Claimant の Authentication が拒否された場合, Verifier は, Attacker が事前に Authenticate できた場合に備えて Claimant に警告してもよい(MAY). また, Verifier は, OTP の重複使用の試行について, 既存セッションの中にいる Subscriber に警告してもよい(MAY).

時間ベースの OTP [TOTP] は, ネットワーク遅延と OTP のユーザー入力のための許容値, それに加え Authenticator が寿命の間に持つはずの両方向のクロックのずれを考慮した上で決定される, 定義されたライフタイムを持つこととなる(SHALL).

Authenticator Output または Activation Secret の Entropy が 64 ビット未満の場合, Verifier は, Sec. 5.2.2 で説明されている通り, Subscriber Account で試行できる Authentication の失敗回数を効果的に制限するレート制限メカニズムを実装することとなる(SHALL).

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticator は, ディスク上またはその他の “ソフト” メディアに格納された Cryptographic Key である. Authentication は, Key の所有と制御を証明することによって成し遂げられる. Authenticator Output は, 特定の暗号プロトコルに大きく依存するが, 通常は何らかのタイプの署名付きメッセージである. Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticator は something you have である.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticators

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticator は, 1つかそれ以上の一意の Secret Key を Authenticator にカプセル化する. Key は, Authenticator アプリケーションが利用可能な, 適切に安全なストレージ (例: キーチェーンストレージ, TPM, または可能であれば TEE) に格納することとなる(SHALL). Key は, アクセスを必要とするデバイス上のそれらのソフトウェアコンポーネントのみに Key へのアクセスを制限するアクセスコントロールを使用して, 無許可の開示から強力に保護されることとなる(SHALL).

Cryptographic Hardware Authenticator の要件を満たさない, 外付けの Cryptographic Authenticator (例: Private Key のエクスポートを許可するメカニズムを持つもの) も, Cryptographic Software Authenticator と見なされる. それらは Sec. 5.2.12 の Connected Authenticator の要件を満たすこととなる(SHALL).

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Verifiers

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Verifier の要件は, Sec. 5.1.7.2 で述べられる Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Verifier と同様である.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Devices

Single-Factor Cryptographic デバイスは, 保護された Cryptographic Key を使用して暗号的操作を実行し, ユーザーエンドポイントへの直接接続を介して Authenticator Output を提供するハードウェアデバイスである. デバイスは, 組み込みの Symmetric または Asymmetric Cryptographic Key を使用し, 二番目の要素による Activation を必要としない. Authentication は, Authentication Protocol を介してデバイスの所有を証明することによって成し遂げられる. Authenticator Output は, ユーザーエンドポイントへの直接接続によって提供され, また特定の暗号デバイスとプロトコルに大きく依存するが, 通常は何らかのタイプの署名付きメッセージである. Single-Factor Cryptographic デバイスは something you have である.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Authenticators

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Authenticator は, 1つかそれ以上の一意の Secret Key を, エクスポート機能を持つことはない(SHALL NOT)(つまり,デバイスから削除できない) Authenticator にカプセル化するために耐タンパー性ハードウェアを使用する. この Authenticator は, Sec. 5.2.12 に指定された通り, Authenticator とエンドポイントの間の直接的なインターフェース(例: USB ポートや保護されたワイヤレス接続)を通じて提示された Challenge Nonce に署名するために Secret Key を使用することで動作する. あるいは, Authenticator は, ユーザーエンドポイントそれ自体に統合された適切に安全なプロセッサであってもよい.

Secret Key とそのアルゴリズムは, 少なくとも [SP800-131A] の最新リビジョンで指定されている最小のセキュリティの長さを提供することとなる(SHALL)(発行日現在で 112 ビット). Challenge Nonce は, 少なくとも 64 ビットの長さとなる(SHALL). Approved Cryptography を使用することとなる(SHALL).

Cryptographic Device Authenticator は, 暗号デバイスによる組み込みの Authentication Secret によって, より大きな保護がもたらされるため, Cryptographic Software Authenticator とは異なる. 暗号デバイスと見なされるために, Authenticator は, ハードウェアの別の部分または組み込みプロセッサ, または実行環境 (例: セキュア エレメント, Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), Trusted Platform Module (TPM))のいずれかとなる(SHALL). これらのハードウェア Authenticator または組み込みプロセッサは, ラップトップやモバイルデバイス上の CPU などのホストプロセッサからは分離される. Cryptographic Device Authenticator は, ホストプロセッサへの Authentication Secret のエクスポートを禁止するように設計されることとなり(SHALL), Secret の抽出が許されるようにホストプロセッサによって再プログラムを行えるようになることはない(SHALL NOT). Authenticator は, Authenticator が使用されている AAL に適合する [FIPS140] の要件の対象となる.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Authenticator は, 動作するために物理的な入力 (例: ボタンを押す) を要求する必要がある(SHOULD). これは, デバイスが接続されているエンドポイントが侵害された場合に発生する可能性がある, デバイスの意図しない動作に対する防御を提供する.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Verifiers

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Verifier は, Challenge Nonce を生成し, それを対象の Authenticator に送信し, デバイスの所有を検証するために Authenticator Output を使用する. Authenticator Output は, 特定の暗号デバイスとプロトコルに大きく依存するが, 通常は何らかのタイプの署名付きメッセージである.

Verifier は, それぞれの Authenticator に対応する Symmetric または Asymmetric Cryptographic Key のいずれかを持つ. 両タイプの鍵は変更から保護されることとなる(SHALL)が, Symmetric Key はさらに, アクセスを必要とするデバイス上のそれらのソフトウェアコンポーネントのみに Key へのアクセスを制限するアクセスコントロールを使用して, 無許可の開示から強力に保護されることとなる(SHALL).

Challenge Nonce は, 長さが少なくとも 64 ビットとなり(SHALL), Authenticator のライフタイムにわたって, または統計的に一意となる(SHALL)(つまり, Approved Random Bit Generator [SP800-90Ar1] を使用して生成される). Verification 操作は, Approved Cryptography を使用することとなる(SHALL).

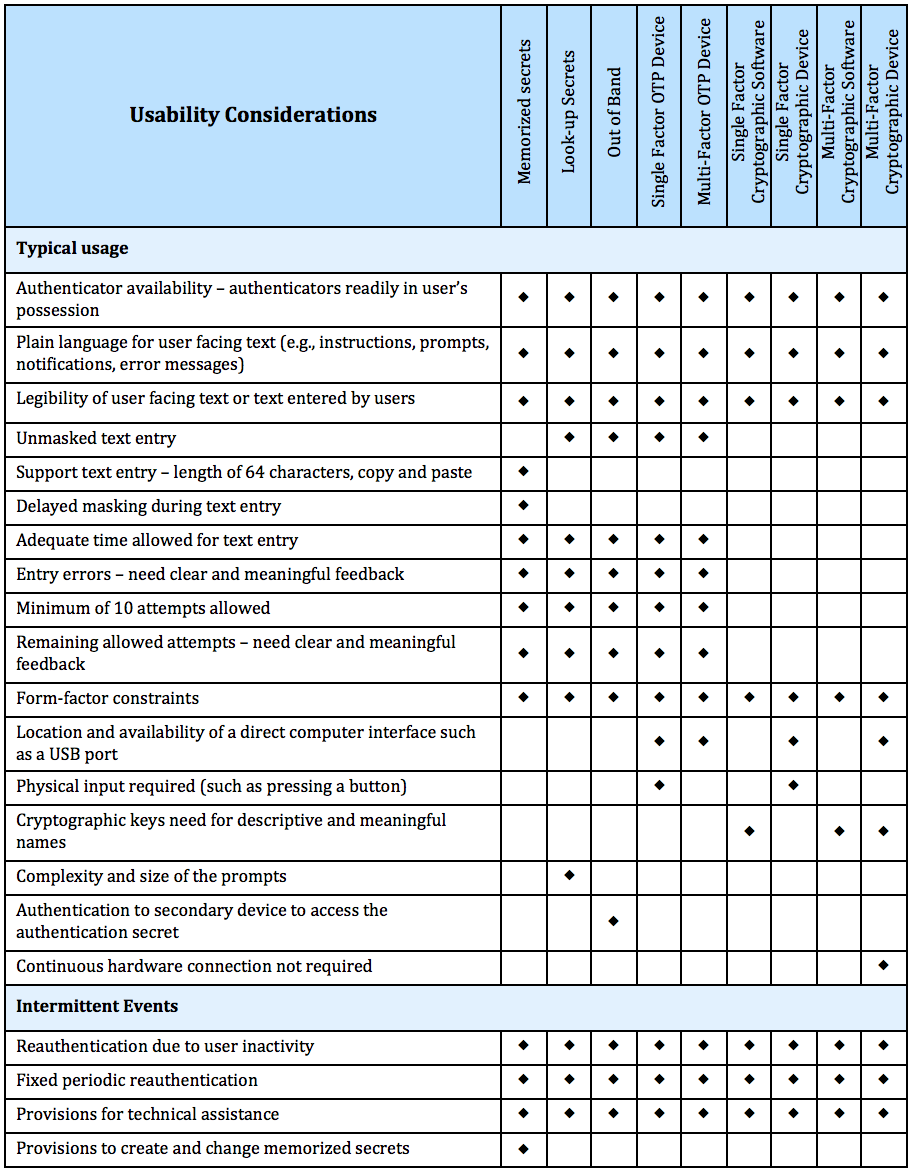

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software