Sun, 05 Mar 2023 05:16:25 +0000

ABSTRACT

本ガイドライン群は, Digital Identity サービスを実装する連邦機関に対する技術的要件を提供するものであり, それ以外の条件下での標準仕様の開発・利用に対する制約を意図したものではない. 本ガイドライン群は, 政府機関がネットワークを介して提供する情報システムを利用するユーザー (従業員, 委託先, 私人など) の Identity Proofing および Authentication について言及している. それぞれのガイドラインが Identity Proofing, Registration, Authenticator, Management Process, Authentication Protocol, Federation および関連する Assertion の各エリアにおいて技術要件を定義する. 本ドキュメントの発行をもって, 本ドキュメントは既存の NIST Special Publication 800-63-3 を置き換えるものとする.

Keywords

authentication; authentication assurance; authenticator; assertions; credential service provider; digital authentication; digital credentials; identity proofing; federation; passwords; PKI.

翻訳者

- 車井 登

- Transmit Security

ABSTRACT

本ガイドライン群は, Digital Identity サービスを実装する連邦機関に対する技術的要件を提供するものであり, それ以外の条件下での標準仕様の開発・利用に対する制約を意図したものではない. 本ガイドライン群は, 政府機関がネットワークを介して提供する情報システムを利用するユーザー (従業員, 委託先, 私人など) の Identity Proofing および Authentication について言及している. それぞれのガイドラインが Identity Proofing, Registration, Authenticator, Management Process, Authentication Protocol, Federation および関連する Assertion の各エリアにおいて技術要件を定義する. 本ドキュメントの発行をもって, 本ドキュメントは既存の NIST Special Publication 800-63-3 を置き換えるものとする.

Keywords

authentication; authentication assurance; authenticator; assertions; credential service provider; digital authentication; digital credentials; identity proofing; federation; passwords; PKI.

Note to Reviewers

The rapid proliferation of online services over the past few years has heightened the need for reliable, equitable, secure, and privacy-protective digital identity solutions.

Revision 4 of NIST Special Publication 800-63, Digital Identity Guidelines, intends to respond to the changing digital landscape that has emerged since the last major revision of this suite was published in 2017 — including the real-world implications of online risks. The guidelines present the process and technical requirements for meeting digital identity management assurance levels for identity proofing, authentication, and federation, including requirements for security and privacy as well as considerations for fostering equity and the usability of digital identity solutions and technology.

Taking into account feedback provided in response to our June 2020 Pre-Draft Call for Comments, as well as research conducted into real-world implementations of the guidelines, market innovation, and the current threat environment, this draft seeks to:

- Advance Equity: This draft seeks to expand upon the risk management content of previous revisions and specifically mandates that agencies account for impacts to individuals and communities in addition to impacts to the organization. It also elevates risks to mission delivery – including challenges to providing services to all people who are eligible for and entitled to them – within the risk management process and when implementing digital identity systems. Additionally, the guidance now mandates continuous evaluation of potential impacts across demographics, provides biometric performance requirements, and additional parameters for the responsible use of biometric-based technologies, such as those that utilize face recognition.

- Emphasize Optionality and Choice for Consumers: In the interest of promoting and investigating additional scalable, equitable, and convenient identify verification options, including those that do and do not leverage face recognition technologies, this draft expands the list of acceptable identity proofing alternatives to provide new mechanisms to securely deliver services to individuals with differing means, motivations, and backgrounds. The revision also emphasizes the need for digital identity services to support multiple authenticator options to address diverse consumer needs and secure account recovery.

- Deter Fraud and Advanced Threats: This draft enhances fraud prevention measures from the third revision by updating risk and threat models to account for new attacks, providing new options for phishing resistant authentication, and introducing requirements to prevent automated attacks against enrollment processes. It also opens the door to new technology such as mobile driver’s licenses and verifiable credentials.

- Address Implementation Lessons Learned: This draft addresses areas where implementation experience has indicated that additional clarity or detail was required to effectively operationalize the guidelines. This includes re-working the federation assurance levels, providing greater detail on Trusted Referees, clarifying guidelines on identity attribute validation sources, and improving address confirmation requirements.

NIST is specifically interested in comments on and recommendations for the following topics:

Identity Proofing and Enrollment

- NIST sees a need for inclusion of an unattended, fully remote Identity Assurance Level (IAL) 2 identity proofing workflow that provides security and convenience, but does not require face recognition. Accordingly, NIST seeks input on the following questions:

- What technologies or methods can be applied to develop a remote, unattended IAL2 identity proofing process that demonstrably mitigates the same risks as the current IAL2 process?

- Are these technologies supported by existing or emerging technical standards?

- Do these technologies have established metrics and testing methodologies to allow for assessment of performance and understanding of impacts across user populations (e.g., bias in artificial intelligence)?

- What methods exist for integrating digital evidence (e.g., Mobile Driver’s Licenses, Verifiable Credentials) into identity proofing at various identity assurance levels?

- What are the impacts, benefits, and risks of specifying a set of requirements for CSPs to establish and maintain fraud detection, response, and notification capabilities?

- Are there existing fraud checks (e.g., date of death) or fraud prevention techniques (e.g., device fingerprinting) that should be incorporated as baseline normative requirements? If so, at what assurance levels could these be applied?

- How might emerging methods such as fraud analytics and risk scoring be further researched, standardized, measured, and integrated into the guidance in the future?

- What accompanying privacy and equity considerations should be addressed alongside these methods?

- Are current testing programs for liveness detection and presentation attack detection sufficient for evaluating the performance of implementations and technologies?

- What impacts would the proposed biometric performance requirements for identity proofing have on real-world implementations of biometric technologies?

Risk Management

- What additional guidance or direction can be provided to integrate digital identity risk with enterprise risk management?

- How might equity, privacy, and usability impacts be integrated into the assurance level selection process and digital identity risk management model?

- How might risk analytics and fraud mitigation techniques be integrated into the selection of different identity assurance levels? How can we qualify or quantify their ability to mitigate overall identity risk?

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

- Are emerging authentication models and techniques – such as FIDO passkey, Verifiable Credentials, and mobile driver’s licenses – sufficiently addressed and accommodated, as appropriate, by the guidelines? What are the potential associated security, privacy, and usability benefits and risks?

- Are the controls for phishing resistance as defined in the guidelines for AAL2 and AAL3 authentication clear and sufficient?

- How are session management thresholds and reauthentication requirements implemented by agencies and organizations? Should NIST provide thresholds or leave session lengths to agencies based on applications, users, and mission needs?

- What impacts would the proposed biometric performance requirements for this volume have on real-world implementations of biometric technologies?

Federation and Assertions

- What additional privacy considerations (e.g., revocation of consent, limitations of use) may be required to account for the use of identity and provisioning APIs that had not previously been discussed in the guidelines?

- Is the updated text and introduction of “bound authenticators” sufficiently clear to allow for practical implementations of federation assurance level (FAL) 3 transactions? What complications or challenges are anticipated based on the updated guidance?

General

- Is there an element of this guidance that you think is missing or could be expanded?

- Is any language in the guidance confusing or hard to understand? Should we add definitions or additional context to any language?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address privacy?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address equity?

- What equity assessment methods, impact evaluation models, or metrics could we reference to better support organizations in preventing or detecting disparate impacts that could arise as a result of identity verification technologies or processes?

- What specific implementation guidance, reference architectures, metrics, or other supporting resources may enable more rapid adoption and implementation of this and future iterations of the Digital Identity Guidelines?

- What applied research and measurement efforts would provide the greatest impact on the identity market and advancement of these guidelines?

Reviewers are encouraged to comment and suggest changes to the text of all four draft volumes of of the NIST SP 800-63-4 suite. NIST requests that all comments be submitted by 11:59pm Eastern Time on March 24, 2023. Please submit your comments to dig-comments@nist.gov. NIST will review all comments and make them available at the NIST Identity and Access Management website. Commenters are encouraged to use the comment template provided on the NIST Computer Security Resource Center website.

Note to Reviewers

The rapid proliferation of online services over the past few years has heightened the need for reliable, equitable, secure, and privacy-protective digital identity solutions.

Revision 4 of NIST Special Publication 800-63, Digital Identity Guidelines, intends to respond to the changing digital landscape that has emerged since the last major revision of this suite was published in 2017 — including the real-world implications of online risks. The guidelines present the process and technical requirements for meeting digital identity management assurance levels for identity proofing, authentication, and federation, including requirements for security and privacy as well as considerations for fostering equity and the usability of digital identity solutions and technology.

Taking into account feedback provided in response to our June 2020 Pre-Draft Call for Comments, as well as research conducted into real-world implementations of the guidelines, market innovation, and the current threat environment, this draft seeks to:

- Advance Equity: This draft seeks to expand upon the risk management content of previous revisions and specifically mandates that agencies account for impacts to individuals and communities in addition to impacts to the organization. It also elevates risks to mission delivery – including challenges to providing services to all people who are eligible for and entitled to them – within the risk management process and when implementing digital identity systems. Additionally, the guidance now mandates continuous evaluation of potential impacts across demographics, provides biometric performance requirements, and additional parameters for the responsible use of biometric-based technologies, such as those that utilize face recognition.

- Emphasize Optionality and Choice for Consumers: In the interest of promoting and investigating additional scalable, equitable, and convenient identify verification options, including those that do and do not leverage face recognition technologies, this draft expands the list of acceptable identity proofing alternatives to provide new mechanisms to securely deliver services to individuals with differing means, motivations, and backgrounds. The revision also emphasizes the need for digital identity services to support multiple authenticator options to address diverse consumer needs and secure account recovery.

- Deter Fraud and Advanced Threats: This draft enhances fraud prevention measures from the third revision by updating risk and threat models to account for new attacks, providing new options for phishing resistant authentication, and introducing requirements to prevent automated attacks against enrollment processes. It also opens the door to new technology such as mobile driver’s licenses and verifiable credentials.

- Address Implementation Lessons Learned: This draft addresses areas where implementation experience has indicated that additional clarity or detail was required to effectively operationalize the guidelines. This includes re-working the federation assurance levels, providing greater detail on Trusted Referees, clarifying guidelines on identity attribute validation sources, and improving address confirmation requirements.

NIST is specifically interested in comments on and recommendations for the following topics:

Identity Proofing and Enrollment

- NIST sees a need for inclusion of an unattended, fully remote Identity Assurance Level (IAL) 2 identity proofing workflow that provides security and convenience, but does not require face recognition. Accordingly, NIST seeks input on the following questions:

- What technologies or methods can be applied to develop a remote, unattended IAL2 identity proofing process that demonstrably mitigates the same risks as the current IAL2 process?

- Are these technologies supported by existing or emerging technical standards?

- Do these technologies have established metrics and testing methodologies to allow for assessment of performance and understanding of impacts across user populations (e.g., bias in artificial intelligence)?

- What methods exist for integrating digital evidence (e.g., Mobile Driver’s Licenses, Verifiable Credentials) into identity proofing at various identity assurance levels?

- What are the impacts, benefits, and risks of specifying a set of requirements for CSPs to establish and maintain fraud detection, response, and notification capabilities?

- Are there existing fraud checks (e.g., date of death) or fraud prevention techniques (e.g., device fingerprinting) that should be incorporated as baseline normative requirements? If so, at what assurance levels could these be applied?

- How might emerging methods such as fraud analytics and risk scoring be further researched, standardized, measured, and integrated into the guidance in the future?

- What accompanying privacy and equity considerations should be addressed alongside these methods?

- Are current testing programs for liveness detection and presentation attack detection sufficient for evaluating the performance of implementations and technologies?

- What impacts would the proposed biometric performance requirements for identity proofing have on real-world implementations of biometric technologies?

Risk Management

- What additional guidance or direction can be provided to integrate digital identity risk with enterprise risk management?

- How might equity, privacy, and usability impacts be integrated into the assurance level selection process and digital identity risk management model?

- How might risk analytics and fraud mitigation techniques be integrated into the selection of different identity assurance levels? How can we qualify or quantify their ability to mitigate overall identity risk?

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

- Are emerging authentication models and techniques – such as FIDO passkey, Verifiable Credentials, and mobile driver’s licenses – sufficiently addressed and accommodated, as appropriate, by the guidelines? What are the potential associated security, privacy, and usability benefits and risks?

- Are the controls for phishing resistance as defined in the guidelines for AAL2 and AAL3 authentication clear and sufficient?

- How are session management thresholds and reauthentication requirements implemented by agencies and organizations? Should NIST provide thresholds or leave session lengths to agencies based on applications, users, and mission needs?

- What impacts would the proposed biometric performance requirements for this volume have on real-world implementations of biometric technologies?

Federation and Assertions

- What additional privacy considerations (e.g., revocation of consent, limitations of use) may be required to account for the use of identity and provisioning APIs that had not previously been discussed in the guidelines?

- Is the updated text and introduction of “bound authenticators” sufficiently clear to allow for practical implementations of federation assurance level (FAL) 3 transactions? What complications or challenges are anticipated based on the updated guidance?

General

- Is there an element of this guidance that you think is missing or could be expanded?

- Is any language in the guidance confusing or hard to understand? Should we add definitions or additional context to any language?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address privacy?

- Does the guidance sufficiently address equity?

- What equity assessment methods, impact evaluation models, or metrics could we reference to better support organizations in preventing or detecting disparate impacts that could arise as a result of identity verification technologies or processes?

- What specific implementation guidance, reference architectures, metrics, or other supporting resources may enable more rapid adoption and implementation of this and future iterations of the Digital Identity Guidelines?

- What applied research and measurement efforts would provide the greatest impact on the identity market and advancement of these guidelines?

Reviewers are encouraged to comment and suggest changes to the text of all four draft volumes of of the NIST SP 800-63-4 suite. NIST requests that all comments be submitted by 11:59pm Eastern Time on March 24, 2023. Please submit your comments to dig-comments@nist.gov. NIST will review all comments and make them available at the NIST Identity and Access Management website. Commenters are encouraged to use the comment template provided on the NIST Computer Security Resource Center website.

Purpose

This section is informative.

本書とその関連である[SP800-63A], [SP800-63B], および [SP800-63C] は、Digital Identity サービスを実装するための技術ガイドラインを組織に提示する.

Purpose

This section is informative.

This publication and its companion volumes, [SP800-63A], [SP800-63B], and [SP800-63C], provide technical guidelines to organizations for the implementation of digital identity services.

Introduction

This section is informative.

仮想世界と物理世界の境界線が曖昧になり, デジタルとインターネット技術の急速な拡大と繋がりが進む中, 開発者と消費者は同様に, この変化するハイブリッドエコシステムを, それに伴う機会とリスクも含めて理解することが不可欠となっている. このハイブリッドエコシステムとの関わりは, しばしば Digital Identity (オンライン取引に関わる人物を一意に表現すること) を確立する個人の能力と意思によって決定される.

Digital Identity は, デジタルサービスのコンテキストでは常に一意であるが, すべてのコンテキストで常に個人を一意に特定できるわけではない. さらに, Digital Identity はデジタルサービスのコンテキスト内では一意で明確な意味を持つが, Digital Identity の背後にある個人の現実の身元は知られていない場合がある. 本書では, 「人」は自然人のみを指す (すなわち, 法人を指していない).

Digital Identity の確立は, Digital Identity の保有者と, Digital Transaction の相手側にいる個人, 組織, または システムとの間に信頼を示すことを意図している. しかし, このプロセスには課題がある. 物理的な世界での関係や Transaction と同様に, ミスコミュニケーション, なりすまし, 他人の Digital Identity の詐称, およびその他の Attack の機会が多数存在する. 加えて, 個人のニーズ, 制約, 能力, 嗜好が多岐に渡ることを考えると, デジタルサービスは, 広く永続的に参加できるように, Equity と柔軟性を考慮して設計する必要がある.

Digital Identity に関連するリスクは, 企業への潜在的な影響を超えて広がっており, 企業の意思決定に組み込まれる必要がある. 本書は, 個人, コミュニティ, および他の組織に対するリスクをより強固にかつ明示的に考慮するように努めている. 具体的には, 組織はこの指針を使用しながら, 組織のサイバーセキュリティの目標を優先する Digital Identity に関する決定が, Privacy, Equity, Usability, およびプログラムやサービスを利用する個人の経験を中心とするミッションとビジネスパフォーマンスのその他の指標に関連するものなどにどのように影響するか, または対応する必要があるかを検討する必要がある. ミッションの提供において, 人間中心で継続的に情報を提供するアプローチをとることにより, 組織は, サービスを提供するさまざまな人々との信頼を徐々に築き, 顧客満足度を高め, 問題をより迅速に特定し, 効果的で文化的に適切な是正策を個人に提供する機会を持つことができる.

これらのガイドラインは, 連邦プログラムおよびその他の組織が, Digital Identity 管理をサポートするプロセス, ポリシー, データ, 人, および技術を含む Digital Identity システムに関連するリスクを評価および管理するためのモデルを示している. このモデルは, Identity Proofing, Authentication, および Federation という一連のプロセスによってサポートされている. Identity Proofing は, Subject が特定の物理的人物であることを証明する. Digital Authentication プロセスは, Digital Identity を主張するために使用される 1 つまたは複数の Authenticator の有効性を判断し, デジタルサービスに Access しようとする Subject が, (1) Authentication に使用されている技術を管理しており, (2) 以前にサービスにアクセスした Subject と同一であるという信頼を確立するものである. 最後に, Federation プロセスは, システム間で Authentication をサポートするために Identity 情報を共有することを可能にする.

Identity サービスの構成, モデル, および Availability (可用性) は, SP 800-63 の初版が発表されて以来大幅に変化し, 安全, プライベート, および公平なサービスを多様なユーザーコミュニティに展開する際の考慮事項や課題も変化してきている. この改訂は, 全体的な Digital Identity モデルの下でエンティティが果たすであろう機能に基づいて要件を明確にし発展した Identity サービスの新しいモデルおよびアーキテクチャを促進しながら, これらの課題に対処している.

さらに, 本書は Credential Service Provider (CSP), Verifier, および Relying Party (RP) に対する指針を提供し, Digital Identity サービスの実装のために組織が従うべき Risk Management プロセスを説明し, NIST Risk Management Framework [NISTRMF] およびそれを構成する Special Publication 群を補完するものである. この出版物は, NIST RMF を拡張して, Equity と Usability への配慮を Digital Identity Risk Management プロセスに組み込む方法を概説し, 企業の運用と資産だけでなく, 個人, 他の組織, およびより広く社会への影響を考慮することの重要性を強調している. さらに, Digital Authentication は, 個人の情報への不正アクセスのリスクを軽減することで Privacy 保護をサポートするが, Identity Proofing, Authentication, Authorization, および Federation は, しばしば個人情報の処理を伴うため, これらの機能は Privacy リスクを引き起こす可能性もある. したがって, このガイドラインは, 関連する潜在的な Privacy リスクの軽減を支援するための Privacy 要件および考慮事項を含んでいる.

最後に, 本書は, ネットワーク上のデジタル・システムにアクセスするために対象者の Digital Identity を確立, 維持, および Authenticate するための技術要件と推奨事項を組織に提供しているが, 障壁や悪影響に対処し, Equity を育み, ミッション目標を正常に達成するには, 情報技術チームの権限外のサポートオプションを追加する必要がある場合がある.

Scope & Applicability

すべてのデジタルサービスに Identity Proofing または Authentication が必要なわけではないが, このガイダンスは利用者層 (市民, ビジネス・パートナー, 政府機関など) に関係なく, 何らかのレベルの Digital Identity が必要なすべてのオンライン Transaction に適用される.

本ガイドラインは, 公共サービスにアクセスする市民やコラボレーションスペースにアクセスする民間セクターのパートナーなど, 外部ユーザーとやり取りする組織サービスを主に対象としている. しかし, 職員や契約社員がアクセスする連邦システムにも適用される. Personal Identity Verification (PIV) of Federal Employees and Contractors standard [FIPS201] および対応する一連の Special Publication と組織固有の説明書は, 連邦企業向けにこれらのガイドラインを拡張し, Personal Identity Verification (PIV) カードの発行と管理, 派生 PIV Credential としての追加 Authenticator のバインド, PIV システムでの Federation アーキテクチャおよびプロトコルの使用に関する追加の技術統制および手順を規定している.

本ガイダンスの対象とならない Transaction には, 44 U.S.C. § 3542(b)(2) に定義される国家安全保障システムに関連するものが含まれる. デジタルプロセスでさまざまなレベルの Digital Identity Assurance を必要とする民間部門組織, 州, 地方, および部族の政府は, 必要に応じてこれらの標準の使用を検討することができる.

加えて, オンライン Transaction に使用される一部の Identity は (建物など) 物理的 Access の際にも使用される場合があるが, これらの技術ガイドラインは物理的 Access に対する Subject の Identity は扱っていない. また, 今回の改訂では, 機器間 (ルータ間など) Authentication や Internet of Things (IoT) と呼ばれる相互接続されたデバイスの Identity については明示的に触れていないが, デバイスへの適用可能性を残すため, 可能な限り一般的な Subject に言及するよう記述されている. さらに, Application Programming Interfaces (API) に対する Subject の代理については, 本ガイドラインでは触れていない.

How to Use this Suite of SPs

本ガイドライン群は, Digital Identity を個別要素ごとに分割することで, Authentication の誤りがもたらすネガティブインパクトの軽減に寄与する. Non-federated なシステムでは, 各機関はそれらのうち Identity Assurance Level (IAL) と Authenticator Assurance Level (AAL) という2つの要素を用いるであろう. Federated なシステムでは, それに加えて3つ目の要素となる Federation Assurance Level (FAL) も用いることとなろう. Sec. 5, Digital Identity Risk Management では, Risk Assessment プロセスの詳細と, Risk Assessment の結果が, リスクとミッションに基づいて IAL, AAL, FAL の組み合わせを組織的に選択するための追加のコンテキストをどのように提供するかについて説明する.

ミッションのニーズと並行して, ビジネス, セキュリティ, プライバシーの適切な Risk Management を行うことで, 組織は IAL , AAL , FAL を個別のオプションとして選択することになる. 具体的には, 各機能に対応したレベルを個別に選択することが求められる. 多くのシステムでは, IAL, AAL, およびFALの各レベルが同じ数値になる可能性があるが, これは要件ではなく, 組織は任意のシステムまたはアプリケーションでこれらが同じであると仮定すべきではない.

本ガイドライン群において詳しく扱う Identity Assurance の構成要素は以下の通りである.

- IAL は, Identity Proofing プロセスについて述べる.

- AAL は, Authentication プロセスについて述べる.

- FAL は, RP が Federated Protocol で接続されている場合の Federation プロセスについて述べる.

注: 本ガイドラインでは, IAL , AAL , FAL を総称して, xAL と表記する場合がある.

SP 800-63 は以下のような一連の Vol. から構成される:

SP 800-63 Digital Identity Guidelines : SP 800-63 では, Risk Assesment の方法論, デジタルシステムにおける Authenticator, Credential, Assertion を利用した一般的な Identity Framework の概観, およびリスクベースプロセスに基づく各 Assurance Level の選択方法について述べる. SP 800-63 には normative な資料と informative な資料の両方が含まれている.

[SP800-63A]: 3 つの Identity Assurance Level (IAL) ごとに, リソースへの Access を希望する Applicant の登録と Identity Proofing の要件を規定する. この文書では, Subscriber Account の確立および維持, ならびに Subscriber Account への Authenticator (CSP 発行または Subscriber 提供のいずれか) のバインドに関する Credential Service Providers (CSP) の責務について詳述している.

SP 800-63A contains both normative and informative material.

[SP800-63B]: 3つの Authentication Assurance Level (AAL) のそれぞれで使用できる Authentication プロセス (Authenticator の選択など) の種類に関する推奨事項を規定する. また, 紛失または盗難時の無効化など, Authenticator のライフサイクルに関する推奨事項を記載している.

SP 800-63B contains both normative and informative material.

[SP800-63C]: Authentication プロセスの結果および関連する Identity 情報を機関アプリケーションに伝達するための, Federated Identity Architecture および Assertion の使用に関する要件を規定している. さらに, この文書では, 有効な Authenticated Subject に関する情報を共有するためのプライバシー強化技術を提供し, Subject がデジタルサービスに対して匿名のままで強力な Multi-factor Authentication (MFA) を可能にする方法について説明している.

SP 800-63C contains both normative and informative material.

Enterprise Risk Management Requirements and Considerations

効果的な企業 Risk Management は, 基本的に多分野にまたがるものであり, 多様な要因および Equity の考慮が必要である. Digital Identity Risk Management のコンテキストでは, これらの要因には, 情報セキュリティ, Privacy, Equity, および Usability が含まれるが, これらに限定されるものではない. Risk Management の取り組みでは, 企業の資産および業務だけでなく, 個人, 他の組織, および社会により広く関係するこれらの要因を考慮することが重要である.

Digital Identity に関連する要素を分析する過程で, 組織は, たとえば Privacy または他の法的要件が存在する場合, または Risk Management の結果から組織が追加の対策または他のプロセスの安全策が適切であると判断する場合など, 特定の状況において本書に規定されていない対策が適切であると判断する場合があり得る. 連邦政府機関を含む組織は, 本書で規定されていない補正的または補足的な管理を採用することができる. また, よりセンシティビティの低い機能をより低い Level of Assurance で利用できるように, Digital Service の機能の分割を検討することもできる.

以下に詳述する考慮事項は, 企業の Risk Management 努力を支援し, 情報に基づいた包括的で人間中心 のサービス提供を促進する. この考慮事項のリストはすべてを網羅しているわけではないが, Digital Identity 管理に関連する意思決定に影響を与える可能性がある一連の横断的な要因を取り上げている.

Security

企業組織にとって, 不正アクセス, Availability (可用性) の問題, なりすまし, および他の不正などの Digital Identity セキュリティリスクを評価および管理し, 強力な ID ガバナンスプラクティスを確立することはますます重要となっている. 組織は, このガイダンスを参照しながら, 自分たちが管理し, サービスプロバイダやビジネスパートナーがサービスを提供する個人やコミュニティのために管理する情報および情報システムの Confidentiality (機密性), Integrity (完全性), および Availability (可用性) に対する潜在的な影響を検討する必要がある.

本ガイドラインを導入する連邦政府機関は, Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) of 2014 [FISMA] および関連のNIST標準とガイドラインに基づくものを含む法的責任を遵守する必要がある. NISTは, これらのガイドラインを実施する非連邦組織が, デジタルシステムの安全な運用を確保するために, 同等の規格に従うことを推奨する.

FISMA は, 連邦政府の情報および情報システムを不正なアクセス, 使用, 開示, 破壊, または改ざんから保護するために適切な管理を実施することを連邦機関に求める. NIST RMF [NISTRMF] は, セキュリティ, プライバシー, サイバーサプライチェーンのリスク管理活動をシステム開発のライフサイクルに統合するプロセスを提供する. このガイドラインに基づいてサービスを提供する連邦政府機関や組織は, FISMAや関連するNISTのリスク管理プロセスや出版物の下で要求されるコントロールやプロセスをすでに実施していることを期待している.

これらのガイドラインに基づく Identity, Authentication, および Federation Assurance Level に包含される管理 および要件は, FISMA および RMF に基づいて決定される情報および情報システムの管理を補完するが, 置き換えたり変更することはない.

Privacy

Digital Identity システムを設計, エンジニアリング, および管理する場合, そのシステムが PII を処理 (Processing) するときに個人のプライバシー関連の問題を引き起こす可能性, 問題のあるデータ操作, および問題のあるデータ操作が発生した場合の潜在的な影響を考慮することが不可欠である. さらに, Predictability, Manageability, およびDisassociabilityというプライバシー工学の目標に注目することで, 組織は, 組織のプライバシーポリシーとシステムのプライバシー要件がどのように実装されているかを実証できるように, 特定のシステムに必要な機能の種類を決定することができる.

Privacy Act of 1974, 2010 Edition, [PrivacyAct]は, 連邦機関が記録システムに保持する個人に関する情報の収集, 維持, 使用, 開示に関する一連の公正な情報プラクティスを定めたものである.

Digital Identity 管理プロセスおよびシステムを設計・実装する場合, プライバシー Risk Assessment はこれらのガイドラインに基づく PII Processing に必要となる. そのようなプライバシー Risk Assessment は, OMB Guidance for Implementing the Privacy Provisions of the E-Government Act of 2002 [M-03-22] に基づくPrivacy Impact Assessments の支援に使用できるほか, NIST Special Publication 800-53, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations [SP800-53] からコントロールを選択するためにも使用することができる. さらに, 800-63 の各巻 (63A, 63B, 63C) には, その巻で提示されたプロセス, 管理, 要件の実装に関する詳細なプライバシー要件と考慮事項を示す特定のセクションが含まれている.

Equity

Executive Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government [EO13985] に規定されているように, Equityとは, 黒人, ラテン系, 先住民, ネイティブアメリカン, アジア系アメリカ人, 太平洋諸島民, その他の有色人種, 宗教的少数派の人々, レズビアン, ゲイ, バイセクシャル, トランスジェンダー, クィア (LGBTQ+) の人々, 障害者, 地方に住む人々, その他根強い貧困や不平等から悪影響を受ける人々など, これまでそうした扱いを受けてこなかった, 恵まれないコミュニティに属する個人を含むすべての個人に対する一貫した体系的かつ公正で公平な扱いを意味する.

ヘルスケアなどの重要なサービスを利用する場合, オンライン Transaction に参加できるかどうかは, 多くの場合, Digital Identityを正しく安全に提示できるかどうかに依存している. 米国社会および世界的に存在する広範な格差を考慮すると, 多くの人々が Digital Identity をうまく提示できないか, またはオンラインサービスを利用する際に, より恵まれた人々よりも高い負担に直面し, 重要なサービスやオンラインの世界への幅広い参加から締め出されることになる. 公共サービスにおいては, このような状況は, ミッションを成功させるための直接的なリスクとなる. より広い社会的背景では, デジタルアクセスに関する問題は, 既存の不公平を悪化させ, 歴史的に疎外され, 十分なサービスを受けていないグループに対する排除の体系的なサイクルを継続させる可能性がある.

このガイダンスの読者は, Digital Identity システムおよびプロセスを彼らのニーズを最もよく支援する方法で設計または運用する機会を特定するために, サービスを提供する集団が直面する既存の不公平を考慮することが推奨される. 読者はまた, Digital Identity システムの設計または運用によって, 集団間の格差を含め, これらの集団経験および結果に潜在的または実際の影響を与えることを考慮するよう推奨される.

このガイドラインを実施する連邦政府機関に対し, EO 13985 は, 連邦政府機関が提供するプログラムおよびサービスについて, 十分なサービスを受けていないコミュニティを特定し, それらのプログラムおよびサービスへの公平なアクセスを提供するために, 十分なサービスを受けていないコミュニティに対する制度的障害を特定し対処するよう指示している. EO 13985 の方向性に沿って, 連邦機関は, コミュニティや個人がオンライン給付やサービスへの登録やアクセスに直面する可能性のある障壁を判断するべきである. また, Equity を高めるためにプログラムの変更が必要であるかどうかを確認する必要がある.

Usability

Usability とは, あるシステム, 製品, サービスを, 特定のユーザーが, 特定の使用状況において, 有効性, 効率性, 満足性をもって, 特定の目標を達成するために使用できる程度を指す.

Equity と同様に, Usability には Digital Identity システムまたはプロセスに触れる人々, および彼ら固有の目標や使用状況の理解が必要である. 効果的, 効率的, かつ満足のいく体験を提供するために, このガイダンスの読者は, Enrollment および Authentication のプロセスを通じて各ユーザーが行うインタラクションを考慮する全体的なアプローチを取る必要がある. Digital Identity システムまたはプロセスの設計および開発ライフサイクルを通じて, 適切な使用状況で現実的なシナリオおよびタスクを実行する代表的なユーザーに対する Usability 評価を実施することが重要である.

Digital Identity 管理プロセスは, ユーザーが正しいことを行うのは簡単で, 間違ったことを行うのは困難であり, 間違ったことが起こったときに回復するのが簡単であるように設計および実装されるべきである.

Introduction

This section is informative.

As the line between the virtual world and physical world blurs, and as digital and internet-enabled technologies continue to proliferate and connect, it is imperative that developers and consumers alike understand this changing hybrid ecosystem - including its associated opportunities and risks. Engagement across this ecosystem is often determined by an individual’s ability and willingness to establish a digital identity - the unique representation of a person engaged in an online transaction.

A digital identity is always unique in the context of a digital service but does not always uniquely identify a person in all contexts. Further, while a digital identity may relay unique and specific meaning within the context of a digital service, the real-life identity of the individual behind the digital identity may not be known. For the purpose of this publication, a “person” refers to natural persons only (i.e., not all legal persons.)

Establishing a digital identity is intended to demonstrate trust between the holder of the digital identity and the person, organization, or system on the other side of the digital transaction. However, this process can present challenges. As in relationships and transactions in the physical world, there are multiple opportunities for mistakes, miscommunication, impersonation, and other attacks that fraudulently claim another person’s digital identity. Additionally, given the broad range of individual needs, constraints, capacities, and preferences, digital services must be designed with equity and flexibility in mind to ensure broad and enduring participation.

Risks associated with digital identity stretch beyond the potential impacts to enterprises and should be incorporated into enterprise decision-making. This publication endeavors to more robustly and explicitly account for risks to individuals, communities, and other organizations. Specifically, while using this guidance, organizations should consider how decisions related to digital identity that prioritize organizational cybersecurity objectives might affect or need to accommodate other objectives, such as those related to privacy, equity, usability, and other indicators of mission and business performance that center the experiences of the individuals interacting with programs and services. By taking a human-centered and continuously informed approach to mission delivery, organizations have an opportunity to incrementally build trust with the variety of populations they serve, improve customer satisfaction, identify issues more quickly, and provide individuals with effective and culturally appropriate redress options.

These guidelines lay out a model for federal programs and other organizations to assess and manage risks associated with digital identity systems, including the processes, policies, data, people, and technologies that support digital identity management. The model is supported by a series of processes: identity proofing, authentication, and federation. The identity proofing process establishes that a subject is a specific physical person. The digital authentication process determines the validity of one or more authenticators used to claim a digital identity and establishes confidence that a subject attempting to access a digital service: (1) is in control of the technologies being used for authentication, and (2) is the same subject that previously accessed the service. Finally, the federation process allows for identity information to be shared in support of authentication across systems.

The composition, model, and availability of identity services has significantly changed since the first version of SP 800-63 was released, as have the considerations and challenges of deploying secure, private, and equitable services to diverse user communities. This revision addresses these challenges while facilitating the new models and architectures for identity services that have developed by clarifying requirements based on the function an entity may serve under the overall digital identity model.

Additionally, this publication provides instruction for credential service providers (CSPs), verifiers, and relying parties (RPs) and it describes the risk management processes that organizations should follow for implementing digital identity services and that supplement the NIST Risk Management Framework [NISTRMF] and its component special publications. The publication expands upon the NIST RMF by outlining how equity and usability considerations should be incorporated into digital identity risk management processes and it highlights the importance of considering impacts, not only on the enterprise operations and assets, but also on individuals, other organizations, and, more broadly, society. Further, while digital authentication supports privacy protection by mitigating risks of unauthorized access to individuals’ information, given that identity proofing, authentication, authorization, and federation often involve the processing of individuals’ information, these functions can also create privacy risks. These guidelines, therefore, include privacy requirements and considerations to help mitigate potential associated privacy risks.

Finally, while this publication provides organizations with technical requirements and recommendations for establishing, maintaining, and authenticating the digital identity of subjects in order to access digital systems over a network, additional support options outside the purview of information technology teams may need to be provided to address barriers and adverse impacts, foster equity, and successfully deliver on mission objectives.

Scope & Applicability

Not all digital services require identity proofing or authentication; however, this guidance applies to all online transactions for which some level of digital identity is required, regardless of the constituency (e.g., citizens, business partners, and government entities).

These guidelines primarily focus on organizational services that interact with external users, such as citizens accessing public benefits or private sector partners accessing collaboration spaces. However, it also applies to federal systems accessed by employees and contractors. The Personal Identity Verification (PIV) of Federal Employees and Contractors standard [FIPS201] and its corresponding set of special publications and organization-specific instructions, extend these guidelines for the federal enterprise, providing additional technical controls and processes for issuing and managing Personal Identity Verification (PIV) cards, binding additional authenticators as derived PIV credentials, and using federation architectures and protocols with PIV systems.

Transactions not covered by this guidance include those associated with national security systems as defined in 44 U.S.C. § 3542(b)(2). Private sector organizations and state, local, and tribal governments whose digital processes require varying levels of digital identity assurance may consider the use of these standards where appropriate.

Additionally, these technical guidelines do not address the identity of subjects for physical access (e.g., to buildings), though some identities used for online transactions may also be used for physical access. Additionally, this revision of these guidelines does not explicitly address device identity, often referred to as machine-to-machine (such as router-to-router) authentication or interconnected devices, commonly referred to as the internet of things (IoT), although these guidelines are written to refer to generic subjects wherever possible to leave open the possibility for applicability to devices. Furthermore, these guidelines do not address authorization of access to Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) on behalf of subjects.

How to Use this Suite of SPs

These guidelines support the mitigation of the negative impacts induced by a digital identity error by separating the individual elements of digital identity into discrete, component parts. For non-federated systems, agencies will select two components, referred to as Identity Assurance Level (IAL) and Authentication Assurance Level (AAL). For federated systems, a third component, Federation Assurance Level (FAL), is included. Sec. 5, Digital Identity Risk Management provides details on the risk assessment process and how the results of the risk assessment, with additional context, inform organizational selection of IAL, AAL, and FAL combinations based on risk and mission.

By conducting appropriate risk management for business, security, and privacy, side-by-side with mission needs, organizations will select IAL, AAL, and FAL as distinct options. Specifically, organizations are required to individually select levels corresponding to each function being performed. While many systems could have the same numerical level for each IAL, AAL, and FAL, this is not a requirement and organizations should not assume they will be the same in any given system or application.

The components of identity assurance detailed in these guidelines are as follows:

- IAL refers to the identity proofing process.

- AAL refers to the authentication process.

- FAL refers to the federation process, when the RP is connected through a federated protocol.

Note: When described generically or bundled, these guidelines will refer to IAL, AAL, and FAL as xAL.

SP 800-63 is organized as the following suite of volumes:

SP 800-63 Digital Identity Guidelines: Provides the risk assessment methodology and an overview of general identity frameworks, using authenticators, credentials, and assertions together in a digital system, and a risk-based process of selecting assurance levels. SP 800-63 contains both normative and informative material.

[SP800-63A]: Provides requirements for enrollment and identity proofing of applicants, either remotely or in person, that wish to gain access to resources at each of the three identity assurance levels (IALs). It details the responsibilities of Credential Service Providers (CSPs) with respect to establishing and maintaining subscriber accounts and binding authenticators (either CSP-issued or subscriber-provided) to the subscriber account. SP 800-63A contains both normative and informative material.

[SP800-63B]: Provides recommendations on types of authentication processes, including choices of authenticators, that may be used at each of the three authentication assurance levels (AALs). It also provides recommendations on the lifecycle of authenticators, including invalidation in the event of loss or theft. SP 800-63B contains both normative and informative material.

[SP800-63C]: Provides requirements on the use of federated identity architectures and assertions to convey the results of authentication processes and relevant identity information to an agency application. Further, this volume offers privacy-enhancing techniques to share information about a valid, authenticated subject, and describes methods that allow for strong multi-factor authentication (MFA) while the subject remains pseudonymous to the digital service. SP 800-63C contains both normative and informative material.

Enterprise Risk Management Requirements and Considerations

Effective enterprise risk management is multidisciplinary by default and involves the consideration of a diverse set of factors and equities. In a digital identity risk management context, these factors include, but are not limited to, information security, privacy, equity, and usability. It is important for risk management efforts to weigh these factors as they relate not only to enterprise assets and operations but also to individuals, other organizations, and society more broadly.

During the process of analyzing factors relevant to digital identity, organizations may determine that measures outside of those specified in this publication are appropriate in certain contexts, for instance where privacy or other legal requirements exist or where the output of a risk assessment leads the organization to determine that additional measures or other process safeguards are appropriate. Organizations, including federal agencies, may employ compensating or supplemental controls not specified in this publication. They may also consider partitioning the functionality of a digital service to allow less sensitive functions to be available at a lower level of assurance.

The considerations detailed below support enterprise risk management efforts and encourage informed, inclusive, and human-centric service delivery. While this list of considerations is not exhaustive, it highlights a set of cross-cutting factors likely to impact decision-making associated with digital identity management.

Security

It is increasingly important for enterprise organizations to assess and manage digital identity security risks, such as unauthorized access, availability issues, impersonation, and other types of fraudulent claims, as well as institute strong identity governance practices. As organizations consult this guidance, they should consider potential impacts to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information and information systems that they manage and that their service providers and business partners manage on behalf of the individuals and communities that they serve.

Federal agencies implementing these guidelines need to adhere to their statutory responsibilities, including those under the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) of 2014 [FISMA] and related NIST standards and guidelines. NIST recommends that non-federal organizations implementing these guidelines follow equivalent standards to ensure the secure operation of their digital systems.

FISMA requires federal agencies to implement appropriate controls to protect federal information and information systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, or modification. The NIST RMF [NISTRMF] provides a process that integrates security, privacy, and cyber supply chain risk management activities into the system development life cycle. It is expected that federal agencies and organizations that provide services under these guidelines have already implemented the controls and processes required under FISMA and associated NIST risk management processes and publications.

The controls and requirements encompassed by the identity, authentication, and federation assurance levels under these guidelines augment, but do not replace or alter, the information and information system controls as determined under FISMA and the RMF.

Privacy

When designing, engineering, and managing digital identity systems, it is imperative to consider the potential of that system to create privacy-related problems for individuals when processing PII — a problematic data action — and the potential impact of the problematic data action should it occur. Additionally, by focusing on the privacy engineering objectives of predictability, manageability, and disassociability, organizations can determine the types of capabilities a given system may need to be able to demonstrate how organizational privacy policies and system privacy requirements have been implemented.

The Privacy Act of 1974, 2010 Edition, [PrivacyAct] established a set of fair information practices for the collection, maintenance, use, and disclosure of information about individuals that is maintained by federal agencies in systems of records.

When designing and implementing digital identity management processes and systems, privacy risk assessments are required for PII processing under these guidelines. Such privacy risk assessments can be used to support Privacy Impact Assessments under OMB Guidance for Implementing the Privacy Provisions of the E-Government Act of 2002 [M-03-22] as well as to select controls from NIST Special Publication 800-53, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations [SP800-53]. Further, each volume of 800-63 (63A, 63B, and 63C) contains a specific section providing detailed privacy requirements and considerations for the implementation of the processes, controls, and requirements presented in that volume.

Equity

As defined in Executive Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government [EO13985], equity refers to the consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment, such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality.

A person’s ability to engage in an online transaction, such as accessing a critical service like healthcare, is often dependent on their ability to successfully and safely present a digital identity. Given the broad disparities that exist in the U.S. society and globally, many people are either unable to successfully present a digital identity, or they face a higher degree of burden in navigating online services than their more privileged peers, leaving them locked out of critical services or broader participation in the online world. In a public service context, this poses a direct risk to successful mission delivery. In a broader societal context, challenges related to digital access can exacerbate existing inequities and continue systemic cycles of exclusion for historically marginalized and underserved groups.

Readers of this guidance are encouraged to consider existing inequities faced by the populations they serve to identify opportunities to design or operate digital identity systems and processes in ways that best support their needs. Readers are also encouraged to consider any potential or actual impact to the experiences and outcomes of these populations, including disparities between populations, caused by the design or operation of digital identity systems.

For federal agencies implementing these guidelines, EO 13985 directs federal agencies to identify underserved communities for the programs and services that they provide and to determine and address any systemic barriers to underserved communities to provide equitable access to those programs and services. In alignment with the direction set by EO 13985, federal agencies should determine potential barriers communities and individuals may face to enrollment in and access to online benefits and services. They should also identify whether programmatic changes may be necessary to advance equity.

Usability

Usability refers to the extent to which a system, product, or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use.

Similar to equity, usability requires an understanding of the people interacting with a digital identity system or process, as well as their unique goals and context of use. To provide an effective, efficient, and satisfactory experience, readers of this guidance should take a holistic approach to considering the interactions that each user will engage in throughout the process of enrolling in and authenticating to a service. Throughout the design and development lifecycle of a digital identity system or process, it is important to conduct usability evaluation with representative users performing realistic scenarios and tasks in appropriate context of use.

Digital identity management processes should be designed and implemented so it is easy for users to do the right thing, hard to do the wrong thing, and easy to recover when the wrong thing happens.

Definitions and Abbreviations

用語定義と略語の完全なセットについては, Appendix A を参照のこと.

Definitions and Abbreviations

See Appendix A for a complete set of definitions and abbreviations.

Digital Identity Model

This section is informative.

Overview

SP 800-63 ガイドラインでは, 現在市場で入手可能な技術およびアーキテクチャを反映した Digital Identity モデルが使用されている. これらのモデルにはさまざまな主体および機能があり, 複雑さもさまざまである. 単純なモデルは, Subscriber Account の作成および Attribute の提供などの機能を 1 つの主体の下にグループ化する. より複雑なモデルでは, これらの機能をより多くの主体に分割している. Digital Identity モデルに見られる主体およびその関連機能には, 以下のものがある.

Subject (represented by one of three roles):

- Applicant — Identity Proofing される Subject

- Subscriber — Identity Proofing が完了した, または Authentication が完了した Subject

- Claimant — Authentication される Subject

Credential Service Provider (CSP): Identity サービスへの Applicant の Identity Proofing ,および Subscriber Account への Authenticator の登録を含む機能を持つ, 信頼された主体. Subscriber Account は, Subscriber, Subscriber の Attribute , および関連する Authenticator に関する CSP が確立した記録である. CSP は, 独立したサード・パーティである場合もある.

Relying Party (RP): 通常, Transaction を処理し, 情報またはシステムへの Access を許可するために, Subscriber Account の情報, または Federation を使用する場合の Identity Provider (IdP) Assertion に依存する主体.

Verifier: Authentication Protocol を使用して, Claimant が1 つまたは複数の Authenticator を所有および管理していることを検証することにより, Claimant の身元を確認する機能を有する主体. これを行うには, Verifier は Authenticator と Subscriber Account の紐づきを確認し, Subscriber Account がアクティブであることを確認する必要がある.

Identity Provider (IdP): Federated モデルにおける, CSP と Verifier の両方の機能を実行する主体. IdP は, Subscriber の Authentication と, 1つまたは複数の RP と通信するための Assertion の発行を責務とする.

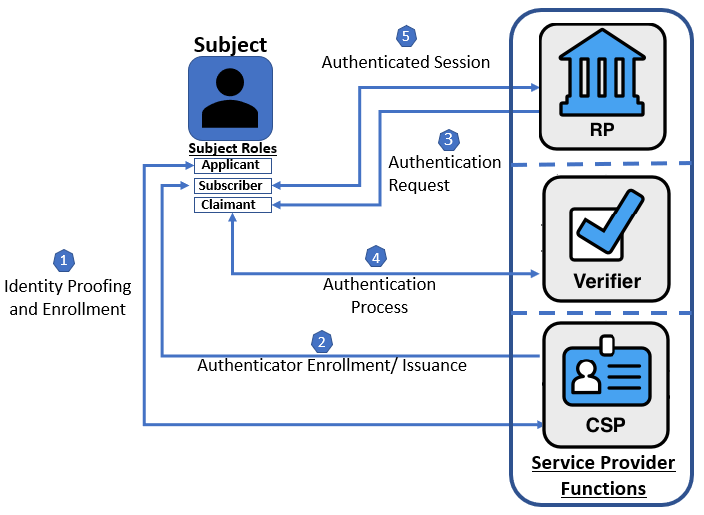

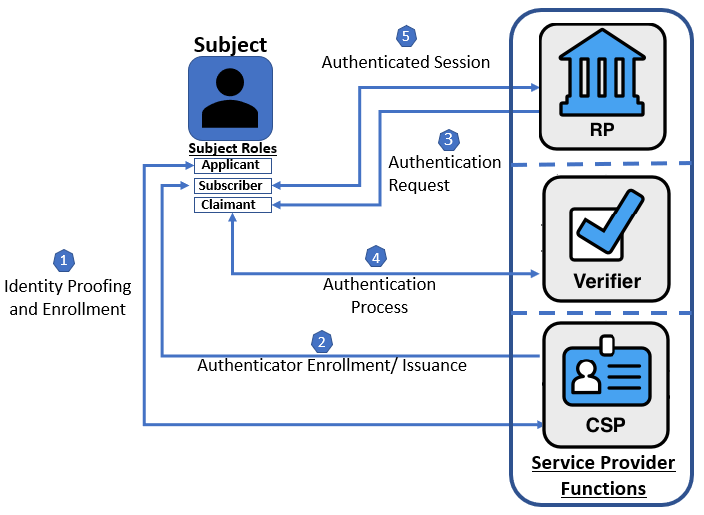

Non-federated Digital Identity モデルを構成する主体および相互作用を, Figure 1 に示す. Federated Digital Identity モデルは Figure 2 に示す.

Figure 1. Non-federated Digital Identity Model Example

Figure 1 はNon-federated モデルでよく見られる相互作用のシーケンスの一例である. 他のシーケンスでも, 同じ機能要件を達成することができる. Identity Proofing および Enrollment のための通常の相互作用のシーケンスは次のとおりである.

- Step 1: Applicantは, Enrollment プロセスを通じて CSP に申請する. CSP は, そのApplicantの身元を証明 (Identity Proof) する.

- Step 2: Proofing に成功すると, Applicant は Identity サービスに Subscriber として Enrollment される.

- Subscriber Account および対応する Authenticator が, CSP と Subscriber の間で確立される. CSP は Subscriber Account, そのステータス, および Enrollment データを維持する. Subscriber は自分の Authenticator を保持する.

Non-federated モデルにおいて, 1つまたは複数の Authenticator を使用して Digital Authentication を実行する際の, 通常の一連のやりとりは以下のとおりである.

- Step 3: RP が Claimant に Authentication を要求する.

- Step 4: Claimantは, Authentication プロセスを通じて, Authenticator の所有と管理を Verifier に証明する.

- Verifier は CSP とやり取りして, Claimant の Identity と Subscriber Account の Authenticator の結びつきを検証し, オプションで追加の Subscriber Attribute を取得する.

- サービスプロバイダの CSP または Verifier の機能は, Subscriberに関する情報を提供する. RP は, 必要とする Attribute を CSP に要求する. RPは, オプションとして, この情報を使用して Authorization の決定を行う.

- Step 5: Subscriber と RP の間に Authenticated Session が確立される.

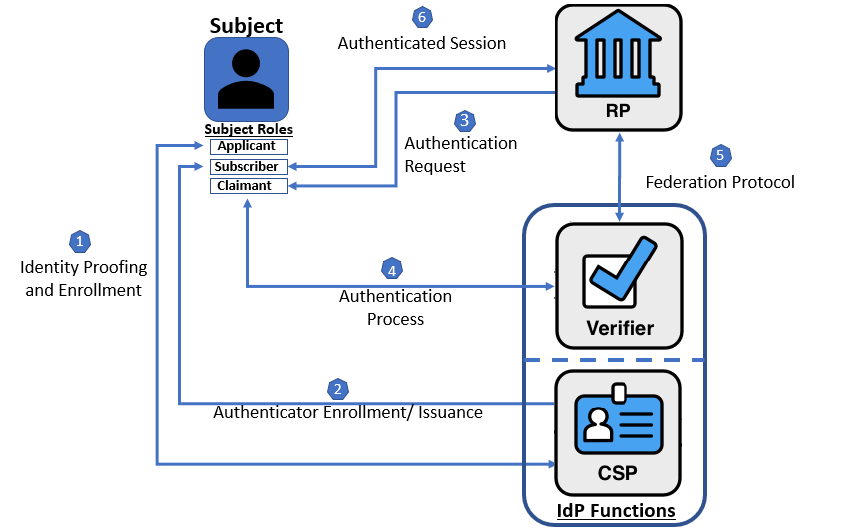

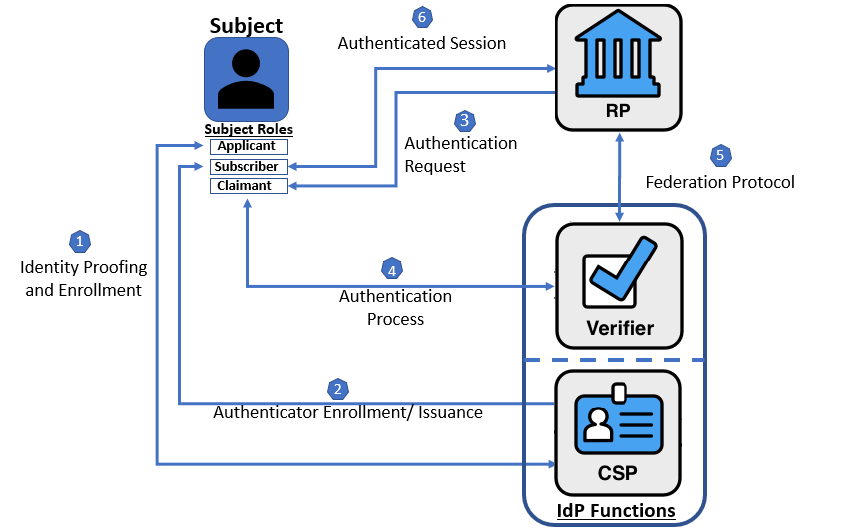

Figure 2. Federated Digital Identity Model Example

Figure 2 は, Federated モデルにおける同じ共通インタラクションの例である.

- Step 1: Applicantは, Enrollment プロセスを通じてIdPに申請する. IdPは, CSP機能を用いて, Applicant の Identity Proofing を行う.

- Step 2: Proofing に成功すると, Applicant は Identity サービスに Subscriber として Enrollment される.

- Subscriber Account と対応する Authenticator が, IdP と Subscriber の間で確立される. IdP は, Subscriber Account とその状態, および収集した Enrollment データを Subscriber Account の存続期間中 (最低限) 保持する. Subscriber は Authenticator を保持する.

Federated モデルで1つ以上の Authenticator を使用してデジタル Authentication を行う際の通常の一連のやり取りは, 以下のとおり:

- Step 3: RP は Claimant に Authentication を要求する. IdP は Federation Protocol を通じて, RP に Assertion と, オプションで追加 Attribute を提供する.

- Step 4: Claimant は Authentication プロセスを通じて, IdPの Verifier 機能に対して Authenticator の所有と管理を証明する.

- IdP 内では, Verifier と CSP の機能が相互に作用し, Claimant の Authenticator と Claimed Subscriber Account にバインドされている Authenticator のバインドを検証し, オプションとして追加の Subscriber Attribute を取得する.

- Step 5: RP と IdP の間の Assertion を含むすべての通信は, Federation プロトコルを通じて行われる.

- Step 6: IdP は RP に Subscriber の Authentication の状況と, 関連する Attribute を提供し, Subscriber と RP の間で Authenticated Session が確立される.

どちらのモデルでも, Verifier は Authentication アクティビティ (たとえば, デジタル証明書の一部の使用など) を完了するために, 常に CSP とリアルタイムで通信する必要はない. したがって, Verifier と CSP の間の繋がりは, 2つのエンティティ間の論理的な繋がりを表している. 一部の実装では, Verifier, RP, およびCSPの機能は分散され, 分離されている場合がある. しかし, これらの機能が同じプラットフォーム上に存在する場合, 機能間のインタラクションは, ネットワークプロトコルを使用するのではなく, 同じシステム上で動作するアプリケーションまたはアプリケーションモジュール間のシグナルとなる.

いずれの場合も, RPは Claimant を Authentication する前に, CSP または IdP に必要な Attribute を要求する必要がある.

以下のセクションでは, Identity Proofing, Authentication, および Federation に関するより詳細な Digital Identity モデルについて説明する.

Enrollment and Identity Proofing

前のセクションでは, 概念的な Digital Identity モデルにおけるエンティティとインタラクションについて紹介した. このセクションでは, Identity Proofing および Enrollment プロセスに関する参加者の関係および責任についての追加的な詳細を説明する.

[SP800-63A], Enrollment and Identity Proofing は, Identity Proofing および Enrollment プロセスに関する一般情報および Normative な要件と, 各 Identity Assurance Level (IAL) に固有の要件を提供する. “No Identity Proofing” レベルである IAL0 に加えて, この文書では Identity Proofing プロセスの相対的な強さを示す 3 つの IAL を定義している.

このステージで Applicant と呼ばれる個人は, CSP に Enroll することを選択する. Applicant の Proof に成功すると, その個人はその CSP の Subscriber として Identity サービスに登録される.

次に, CSP は, 各 Subscriber を一意に識別する Subscriber Account を確立し, その Subscriber Account に登録 (バインド) されたすべての Authenticator を記録する. CSP は, 以下を行うことができる.

- Enrollment 時に, 1つ以上の Authenticator を Subscriber に発行する.

- Subscriber より提供された Authenticator をバインドする, および/または

- 必要に応じて, 後日, Subscriber Account に Authenticator をバインドする.

CSP は一般に, 文書化されたライフサイクルに従って Subscriber Account を維持する. このライフサイクルでは, Subscriber Account の状態に影響する特定のイベント, 活動, および変更が定義される. CSP は一般に, Subscriber に関連する Attribute の正確性と最新性をある程度保証するために, Subscriber Account および関連する Authenticator の有効期間を定める. ステータスに変更があった場合, または Authenticator の有効期限が近づいた場合, および更新要件が満たされた場合, Authenticator は更新および/または再発行されることがある. あるいは, CSP の文書化されたポリシーおよび手続きに従って, Authenticator が無効化され, 破棄されることもある.

Subscriber は, CSP との良好な関係を維持するために Authenticator の管理を維持し, CSP ポリシーを遵守する義務がある.

新しい Authenticator の発行を要求するために, 通常 Subscriber は, 既存の有効期限内の Authenticator を使用して CSP に対して Authentication を行う. Subscriber が有効期限切れまたは失効前に Authenticator の再発行を要求しなかった場合, 新しい Authenticator を取得するために, (完全または省略された形の) Identity Proofing および Enrollment プロセスを再度行うことが要求される場合がある.

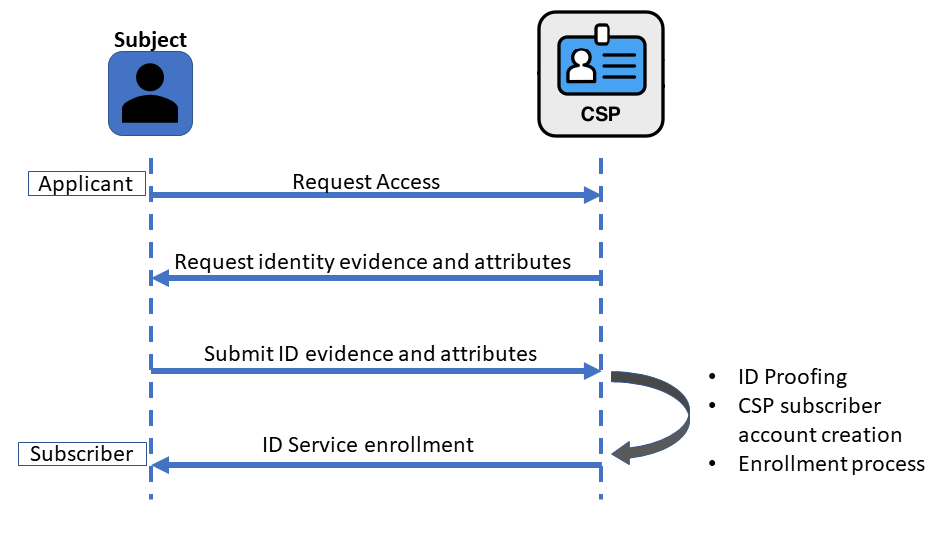

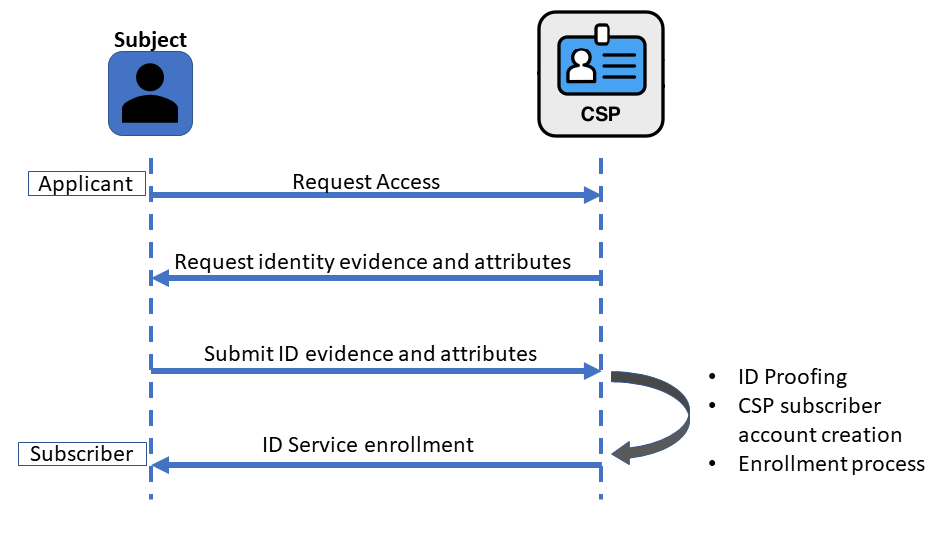

Figure 3 に, Identity Proofing と Enrollment のためのインタラクションの例を示す.

Figure 3. Sample Identity Proofing and Enrollment Digital Identity Model

\clearpage

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

Normative な要件は, [SP800-63B], Authentication and Lifecycle Management を参照のこと.

Authenticators

Authentication システムの古典的パラダイムでは, 3つの要素を Authentication の要とする.

- Something you know (例: Password)

- Something you have (例: IDカード, Cryptographic Key)

- Something you are (例: 指紋またはその他の Biometric 特有のデータ)

Single-factor Authentication は, 上記の要素のうち1つだけを必要とし, 多くの場合 “something you know” を必要とする. 同じ要素が複数ある場合でも, Single-factor Authentication となる. 例えば, ユーザーが作成した PIN とPassword は, どちらも “something you know” であるため, 2つの要素とはみなされない. Multi-factor Authentication (MFA) とは, 2つ以上の異なる要素を使用することを指す. 本ガイドライン群の目的においては, 最高のセキュリティー要件を満たすには, 2つの要素を利用するのが適切である. RP や Verifier は Claimed Identity に対するリスク評価のために, 位置データや Device Identity など, 上記以外のタイプの情報を利用することもありうるが, それらは Authentication Factor とは見なされない.

Digital Authentication では, Claimant は1つまたは複数の Authenticator を保持, 管理する. Authenticator は Subscriber Account にバインドされている. Authenticator には, Claimant が正当な Subscriber であることを証明するために使用できる Secret が含まれている. Claimantは, Authenticator を所有し管理していることを証明することにより, ネットワーク上のシステムまたはアプリケーションに対して Authenticate を行う. Authenticate されると, Claimantは Subscriber と呼ばれる.

Authenticator に含まれる Secret は, Key Pair (Asymmetric Cryptographic Key) または Shared Secret (Symmetric Cryptographic Keys, Memorized Secret を含む) のいずれかに基づいている. Asymmetric Key Pair は, Public Key と関連する Private Key で構成される. Private Key は Authenticator 内に保存され, Authenticator を所有し管理する Claimant のみが使用できる. Public Key Certificate などを通じて Subscriber の Public Key を持つ Verifier は, Authentication プロトコルを使用して Claimant が Authenticator に含まれる関連する Private Key を所有し管理していること, すなわち Subscriber であることを Verify する.

上述したように, Authenticator に格納される Shared Secret は, Symmetric Key または Memorized Secret (例えば, パスワードやPIN)のいずれかである可能性がある. Symmetric Key も Memorized Secret も同様のプロトコルで使用することができるが, 両者の重要な違いの1つは, それらが Claimant にどのように関係するかということである. Symmetric Key は一般にランダムに選択され, ネットワークベースの Guessing Attack を阻止するのに十分な複雑さと長さを持ち, Subscriber が管理するハードウェアまたはソフトウェアに格納される. Memorized Secret は, 一般に, 暗記と入力を容易にするために, Cryptographic Key よりも文字数が少なく, 複雑でない. その結果, Memorized Secret は脆弱性が増加し, それを軽減するために追加の防御を必要とする.

Memorized Secret には, また別のタイプとして, Multi-factor Authenticator の Activation Factor として使用されるものがある. これらは Activation Secret と呼ばれる. Activation Secret は Authentication に使用される保存された Key を復号するために使用されるか, または Authentication Key へのアクセスを提供するためにローカルに保存された Verifier と比較される. いずれの場合も, Activation Secret は, Authenticator とそれに関連するユーザーエンドポイント内に留まる. Activation Secretの例は, PIV カードを Activate するために使用される PIN である.

このガイドラインで使用されているように, Authenticator は常に Secret を含むか Secret を構成している. しかし, 対面での対話に使用される Authentication 方法の中には, Digital Authentication に直接適用されないものがある. たとえば, 物理的な運転免許証は, あなたが持っているもの(something you have)であり, 人間 (例:警備員) に対して Authentication する場合には有用かもしれないが, オンライン・サービス用の Authenticator とはならない.

一般的に使用されている Authentication 方法の中には, Secret を含まない, あるいは Secret を構成しないものがあり, そのため本ガイドラインのもとでは使用できない. 例えば, 以下のようなものである.

- Claimant だけが知っていると思われる質問に回答するよう Claimant に促す知識ベース認証 (Knowledge-Based Authentication) は, Digital Authentication の Secret として認められない.

- また, Biometrics は Secret を構成しないため, Single-factor Authenticator として使用することはできない.

Digital Authentication システムは, 以下の2つの方法のどちらかで複数の要素を内包する.

- 複数の要素が Verifier に提示される.

- ある要素が Verifier に提示されるシークレットを保護するために利用される.

例えば, 上記1は Memorized Secret (something you know) を Out-of-band Device (something you have) と組み合わせることで実現可能である. 両方の Authenticator Output が Verifier に提示され, Claimant の Authentication に使われる. 上記2は, Authenticator と Authenticator Secret は, Claimant が管理する Cryptographic Key (something you have) を含むハードウェアの一部で, Access が指紋 (something you are) で保護されているものである. Biometric Factor と共に使用される場合, Cryptographic Key を使って Claimant を Authenticate するための Output が出力される.

上述のとおり, Biometricsは, Digital Authentication で利用可能なシークレットとはならないため, Single-factor Authentication に使用することはできない. しかし, Biometrics Authentication は, 所持ベースの Authenticator と組み合わせて使用する場合, Multi-factor Authentication の Authentication Factor として使用することができる. Biometric 特性は, Verification の時点で物理的に存在する人の Identity を確認するために使用できる, 固有の個人の Attribute である. これには, 顔の特徴, 指紋, 虹彩パターン, および声紋が含まれるが, これらに限定されない.

Subscriber Accounts

前節で説明したように, Subscriber Account は, 登録プロセスの一部として, Identifier を介して, 1つ以上の Authenticator を Subscriber にバインドする. Subscriber Account は, CSP によって作成, 保存, および維持される. Subscriber Account は, Identity Proofing プロセス中に検証されたすべての Identity Attribute を記録する.

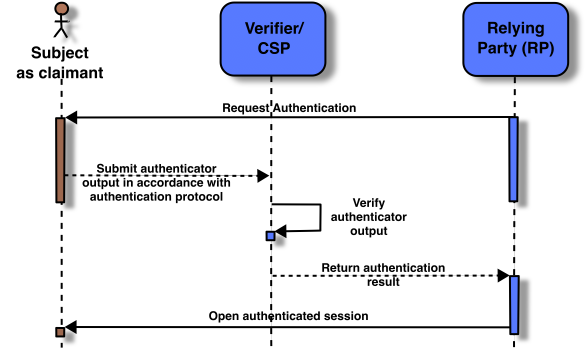

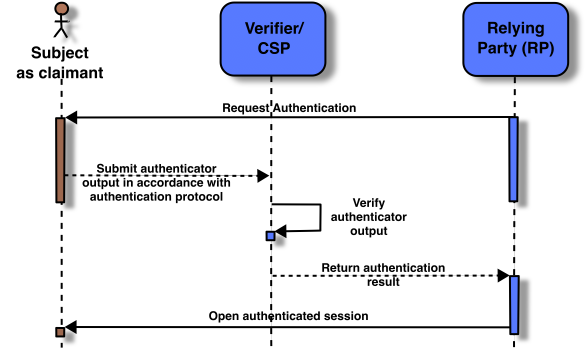

Authentication Process

Authentication プロセスにより, RPは Claimant による自分こそ本人であるという主張を信頼することができる. Figure 4は Authentication プロセスの例を示している. その他のアプローチについては, [SP800-63B], Authentication and Lifecycle Management で説明されてる. このサンプル Authentication プロセスは, RP, Claimant,および Verifier / CSPの間のインタラクションを示す. Verifier は機能的な役割であり, Fig. 4 に示すように, CSP と組み合わせて実装されることが多いが, RP と組み合わせてもよい.

Figure 4. Sample Authentication Process

Authentication プロセスの成功は, Claimant が Subscriber の Identity にバインドされている1つ以上の有効な Authenticator を所有し管理していることを証明する. 一般に, これは Verifier と Claimant の間のインタラクションを含む Authentication Protocol を使用して行われる. インタラクションの具体的な内容は, システム全体のセキュリティを決定する上で非常に重要である. よく設計されたプロトコルは, Authentication の最中および事後において, Claimant と Verifier の間のコミュニケーションの Integrity (完全性) および Confidentiality (機密性) を保護し, Attacker が正当な Verifier であるかのように偽装できてしまった場合の被害を限定的にする.

また, Verifier 側で Attacker による Authentication 試行レートを制限したり不正な試行を遅延させたりすることで, Password や PIN といった Entropy の低いシークレットに対する Online Guessing Attack の影響を軽減できる. 一般的に Online Guessing Attack ではほとんどの試行が失敗するので, その対策は失敗試行数を制限するというような方式となる.

Federation and Assertions

Normative な要件は [SP800-63C], Federation and Assertions を参照のこと.

一般的に Federation という用語は, 異なる Trust ドメイン間の情報共有を含む多くの異なるアプローチに適用されることがある. これらのアプローチは, ドメイン間で共有される情報の種類によって異なる. 一般的な例としては, 以下のようなものがある.

- Identifier の共有 (例: 運転免許証やメールアドレスの利用),

- Authenticator の共有 (例: 複数のアプリケーションにおける PKI Authenticator の利用),

- Identity Assertion の共有 (例: OpenID Connect や SAML のような Federation Protocol),

- Account Attribute の共有 (例: SCIM のような Provisioning Protocol),

- Authorization Decisions の共有 (例: XACML のような Policy Protocol).

SP 800-63 ガイドラインは, 組織が選択する Identity Proofing, Authentication, および Federation アーキテクチャに関して全てを把握しているわけではなく, 組織が独自の要件に従って Digital Identityスキームを展開することも許容している. しかし, 組織が遭遇するシナリオには, 組織または個々のアプリケーションにローカルな Identity サービスを確立するよりも, Federation のほうが効率的かつ効果的である可能性があるものがある. 以下のリストは, 組織が Federation を有効なオプションと見なす可能性のあるシナリオの詳細を示している. これらのリストは検討のために提供されるものであり, 包括的であることは意図していない.

組織は, 以下のいずれかに該当する場合, Federated Identity Assertion を受け入れることを検討すべきである.

- 想定される利用者が, 要求されたAAL以上の Authenticator をすでに持っている.

- 想定されるすべてのユーザーコミュニティをカバーするためには複数のタイプの Authenticator が必要.

- 組織に, Subscriber Account の管理をサポートするための必要なインフラがない (例:アカウントの回復, Authenticator の発行, ヘルプデスクなど).

- RP の実装を変更することなく, プライマリ Authenticator の追加やアップグレードが可能であることが望まれる.

- サポートすべき多くの環境がある. Federation Protocol はネットワークベースであり, 様々なプラットフォームや言語での実装が可能である.

- 想定される利用者は複数のコミュニティから集まっており, それぞれが既存の Identity インフラを持っている.

- アカウントの失効や新しい Authenticator のバインドなど, アカウントのライフサイクルを一元的に管理できることが重要である.

組織は, 以下のいずれかに該当する場合, Federated Identity Attributes の受け入れを検討すべきである.

- Pseudonymity が, サービスに Access する利害関係者に要求される, 必要である, 実行可能である, または重要である.

- サービスへの Access には, 一部の Attribute リストが必要.

- サービスに Access するためには, 少なくとも1つの Derived Attribute Value が必要.

- 組織は, 要求された Attribute の Authoritative Source または Issuing Source ではない.

- Attribute は使用時 (Access 判断など) に一時的に必要となるだけで, 組織がデータを保持する必要はない.

Federation Benefits

Federated アーキテクチャには, 以下のような多くの重要な利点があるが, これらに限定されるものではない.

- ユーザーエクスペリエンスの向上. 例えば, ある個人が一度 Identity proofing すれば, 複数の RP でその Subscriber Account を再利用することができる.

- ユーザー (Authenticator の削減) と組織 (情報技術インフラの削減) 双方にとってのコスト削減.

- 組織が Personal Information を収集, 保管, 廃棄する必要がないため, アプリケーションのデータを最小化できる.

- アカウントに保存されたそのものの値を各アプリケーションにコピーするのではなく, Pseudonymous Identifier や Derived Attribute Value を使用することで, アプリケーションに公開するデータを最小化できる.

- ミッションの実現: 組織は, Identity Management へのリソースの拡大を気にすることなく, ミッションに集中することができる.

以下のセクションでは, 組織がこのタイプのモデルを選択する場合の, Federated Identity アーキテクチャの構成要素について説明する.

Federation Protocols and Assertions

Federation プロトコルでは, ネットワークシステム間で Assertion, Authentication Attribute, Subscriber Attribute を伝達することができる. Federation のシナリオでは, Figure 2 に示すように, CSP は Identity Provider または IdP と呼ばれるサービスを提供する. IdP は, CSP が発行する Authenticator の Verifier として機能する. Federation プロトコルを使用して, IdP は, この Authentication イベントに関する Assertion と呼ばれるメッセージを RP に送信する. Assertion は, Subscriberの Authentication イベントを表す, IdP から RP への検証可能な Statement である. RP は IdP から提供された Assertion を受信して使用するが, RP が Authenticator を直接 Verify することはない.

Federation は, 一般に RP と IdP が単一のエンティティでない場合, または共通の管理下にない場合に使用されるが, さまざまな理由から単一のセキュリティドメイン内でこの技術を適用することができる. RP は, Assertion 内の情報を使用して Subscriber を識別し, RP が管理するリソースへの Access に関する Authorization の決定を行う.

Assertion の例を以下に挙げる.

- Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) Assertion はセキュリティー Assertion を記述するためのマークアップランゲージによって規定される. SAML Assertion は Verifier が RP に対して Claimant の Identity に関するステートメントを生成するために利用される. SAML Assertion にはデジタル署名が施されることもある.

- OpenID Connect Claim は, JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) を使ってセキュリティー Claim および任意でユーザー Claim を記述するために規定される. JSON User Information Claims にはデジタル署名が施されることもある.

- Kerberos Ticket は, Ticket-granting Authority が Symmetric または Asymmetric Key ベースの Key Establishment Schemes を利用し, 2つの Authenticated な主体 にSession Key を発行することを可能にする.

Relying Parties

RP は, オンライン Transaction を行うために, Authentication Protocol の結果を頼りに Subscriber の Identity ないしは Attribute に関する確からしさを確立する. RP は, Subscriber の Federated Identity (Pseudonymous なこともあればそうでないこともある), IAL, AAL, FAL およびその他の要素をもとに, Authorization の決定を行う.

Federation を使用する場合, Verifierは RP の機能ではない. Federation を利用する RP は, Verifier 機能を提供する IdP から Assertion を受け取り, その Assertion が RP の信頼する IdP から来たことを確認する. RP は, Assertion に含まれる Personal Attribute や有効期限などの追加情報も処理する. RP は, Verifier から提示された特定の Assertion が, IAL, AAL, FAL にかかわらず, RP の確立したシステム Access の基準を満たしているかどうかを判断する最終裁定者となる.

Digital Identity Model

This section is informative.

Overview

The SP 800-63 guidelines use digital identity models that reflect technologies and architectures currently available in the market. These models have a variety of entities and functions and vary in complexity. Simple models group functions, such as creating subscriber accounts and providing attributes, under a single entity. More complex models separate these functions among a larger number of entities. The entities and their associated functions found in digital identity models include:

Subject (represented by one of three roles):

- Applicant — the subject to be identity proofed

- Subscriber — the subject that has successfully completed the identity proofing process or has successfully completed authentication

- Claimant — the subject to be authenticated

Credential Service Provider (CSP): A trusted entity whose functions include identity proofing applicants to the identity service and the registration of authenticators to subscriber accounts. A subscriber account is the CSP’s established record of the subscriber, the subscriber’s attributes, and associated authenticators. A CSP may be an independent third party.

Relying Party (RP): An entity that relies upon the information in the subscriber account, or an identity provider (IdP) assertion when using federation, typically to process a transaction or grant access to information or a system.

Verifier: An entity whose function is to verify the claimant’s identity by verifying the claimant’s possession and control of one or more authenticators using an authentication protocol. To do this, the verifier needs to confirm the binding of the authenticators with the subscriber account and check that the subscriber account is active.

Identity Provider (IdP): An entity in a federated model that performs both the CSP and Verifier functions. The IdP is responsible for authenticating the subscriber and issuing assertions to communicate with one or more RPs.

The entities and interactions that comprise the non-federated digital identity model are illustrated in Figure 1. The federated digital identity model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Non-federated Digital Identity Model Example

Figure 1 shows an example of a common sequence of interactions in the non-federated model. Other sequences could also achieve the same functional requirements. The usual sequence of interactions for identity proofing and enrollment activities is as follows:

- Step 1: An applicant applies to a CSP through an enrollment process. The CSP identity proofs that applicant.

- Step 2: Upon successful proofing, the applicant is enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber.

- A subscriber account and corresponding authenticators are established between the CSP and the subscriber. The CSP maintains the subscriber account, its status, and the enrollment data. The subscriber maintains their authenticators.

The usual sequence of interactions involved in using one or more authenticators to perform digital authentication in the non-federated model is as follows:

- Step 3: The RP requests authentication from the claimant.

- Step 4: The claimant proves possession and control of the authenticators to the verifier through an authentication process.

- The verifier interacts with the CSP to verify the binding of the claimant’s identity to their authenticators in the subscriber account and to optionally obtain additional subscriber attributes.

- The CSP or verifier functions of the service provider provide information about the subscriber. The RP requests the attributes it requires from the CSP. The RP, optionally, uses this information to make authorization decisions.

- Step 5: An authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

Figure 2. Federated Digital Identity Model Example

Figure 2 shows an example of those same common interactions in a federated model.

- Step 1: An applicant applies to an IdP through an enrollment process. Using its CSP function, the IdP identity proofs the applicant.

- Step 2: Upon successful proofing, the applicant is enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber.

- A subscriber account and corresponding authenticators are established between the IdP and the subscriber. The IdP maintains the subscriber account, its status, and the enrollment data collected for the lifetime of the subscriber account (at a minimum). The subscriber maintains their authenticators.

The usual sequence of interactions involved in using one or more authenticators in the federated model to perform digital authentication is as follows:

- Step 3: The RP requests authentication from the claimant. The IdP provides an assertion and optionally additional attributes to the RP through a federation protocol.

- Step 4: The claimant proves possession and control of the authenticators to the verifier function of the IdP through an authentication process.

- Within the IdP, the verifier and CSP functions interact to verify the binding of the claimant’s authenticators with those bound to the claimed subscriber account and optionally to obtain additional subscriber attributes.

- Step 5: All communication, including assertions, between the RP and the IdP happens through federation protocols.

- Step 6: The IdP provides the RP with the authentication status of the subscriber and relevant attributes and an authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

For both models, the verifier does not always need to communicate in real time with the CSP to complete the authentication activity (e.g., some uses of digital certificates). Therefore, the line between the verifier and the CSP represents a logical link between the two entities. In some implementations, the verifier, RP, and CSP functions may be distributed and separated. However, if these functions reside on the same platform, the interactions between the functions are signals between applications or application modules running on the same system rather than using network protocols.

In all cases, the RP should request the attributes it requires from a CSP or IdP before authenticating the claimant.

The following sections provide more detailed digital identity models for identity proofing, authentication, and federation.

Enrollment and Identity Proofing

The previous section introduced the entities and interactions in the conceptual digital identity model. This section provides additional details regarding the participants’ relationships and responsibilities with respect to identity proofing and enrollment processes.

[SP800-63A], Enrollment and Identity Proofing provides general information and normative requirements for the identity proofing and enrollment processes as well as requirements specific to identity assurance levels (IALs). In addition to a “no identity proofing” level, IAL0, this document defines three IALs that indicate the relative strength of an identity proofing process.

An individual, referred to as an applicant at this stage, opts to enroll with a CSP. If the applicant is successfully proofed, the individual is then enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber of that CSP.

The CSP then establishes a subscriber account to uniquely identify each subscriber and record any authenticators registered (bound) to that subscriber account. The CSP may:

- issue one or more authenticators to the subscriber at the time of enrollment,

- bind authenticators provided by the subscriber, and/or

- bind authenticators to the subscriber account at a later time as needed.

CSPs generally maintain subscriber accounts according to a documented lifecycle, which defines specific events, activities, and changes that affect the status of a subscriber account. CSPs generally limit the lifetime of a subscriber account and any associated authenticators in order to ensure some level of accuracy and currency of attributes associated with a subscriber. When there is a status change or when the authenticators near expiration and any renewal requirements are met, they may be renewed and/or re-issued. Alternately, the authenticators may be invalidated and destroyed according to the CSPs written policy and procedures.

Subscribers have a duty to maintain control of their authenticators and comply with CSP policies in order to remain in good standing with the CSP.

In order to request issuance of a new authenticator, typically the subscriber authenticates to the CSP using their existing, unexpired authenticators. If the subscriber fails to request authenticator re-issuance prior to their expiration or revocation, they may be required to repeat the identity proofing (either complete or abbreviated) and enrollment processes in order to obtain a new authenticator.

Figure 3 shows a sample of interactions for identity proofing and enrollment.

Figure 3. Sample Identity Proofing and Enrollment Digital Identity Model

\clearpage

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

Normative requirements can be found in [SP800-63B], Authentication and Lifecycle Management.

Authenticators

The classic paradigm for authentication systems identifies three factors as the cornerstones of authentication:

- Something you know (e.g., a password)

- Something you have (e.g., an ID badge or a cryptographic key)

- Something you are (e.g., a fingerprint or other biometric characteristic data)

Single-factor authentication requires only one of the above factors, most often “something you know”. Multiple instances of the same factor still constitute single-factor authentication. For example, a user generated PIN and a password do not constitute two factors as they are both “something you know.” Multi-factor authentication (MFA) refers to the use of more than one distinct factor. For the purposes of these guidelines, using two factors is adequate to meet the highest security requirements. Other types of information, such as location data or device identity, may also be used by a verifier to evaluate the risk in a claimed identity but they are not considered authentication factors.

In digital authentication, the claimant possesses and controls one or more authenticators. The authenticators will have been bound with the subscriber account. The authenticators contain secrets the claimant can use to prove they are a legitimate subscriber. The claimant authenticates to a system or application over a network by demonstrating they have possession and control of the authenticator. Once authenticated, the claimant is referred to as a subscriber.

The secrets contained in an authenticator are based on either key pairs (asymmetric cryptographic keys) or shared secrets (including symmetric cryptographic keys and memorized secrets). Asymmetric key pairs are comprised of a public key and a related private key. The private key is stored on the authenticator and is only available for use by the claimant who possesses and controls the authenticators. A verifier that has the subscriber’s public key, for example through a public key certificate, can use an authentication protocol to verify the claimant has possession and control of the associated private key contained in the authenticators and, therefore, is a subscriber.

As mentioned above, shared secrets stored on an authenticator may be either symmetric keys or memorized secrets (e.g., passwords and PINs). While both keys and memorized secrets can be used in similar protocols, one important difference between the two is how they relate to the claimant. Symmetric keys are generally chosen at random and are complex and long enough to thwart network-based guessing attacks, and stored in hardware or software that the subscriber controls. Memorized secrets typically have fewer characters and less complexity than cryptographic keys to facilitate memorization and ease of entry. The result is that memorized secrets have increased vulnerabilities that require additional defenses to mitigate.