Digital Identity Model

This section is informative.

Overview

The SP 800-63 guidelines use digital identity models that reflect technologies and architectures currently available in the market. These models have a variety of entities and functions and vary in complexity. Simple models group functions, such as creating subscriber accounts and providing attributes, under a single entity. More complex models separate these functions among a larger number of entities. The entities and their associated functions found in digital identity models include:

Subject (represented by one of three roles):

- Applicant — the subject to be identity proofed

- Subscriber — the subject that has successfully completed the identity proofing process or has successfully completed authentication

- Claimant — the subject to be authenticated

Credential Service Provider (CSP): A trusted entity whose functions include identity proofing applicants to the identity service and the registration of authenticators to subscriber accounts. A subscriber account is the CSP’s established record of the subscriber, the subscriber’s attributes, and associated authenticators. A CSP may be an independent third party.

Relying Party (RP): An entity that relies upon the information in the subscriber account, or an identity provider (IdP) assertion when using federation, typically to process a transaction or grant access to information or a system.

Verifier: An entity whose function is to verify the claimant’s identity by verifying the claimant’s possession and control of one or more authenticators using an authentication protocol. To do this, the verifier needs to confirm the binding of the authenticators with the subscriber account and check that the subscriber account is active.

Identity Provider (IdP): An entity in a federated model that performs both the CSP and Verifier functions. The IdP is responsible for authenticating the subscriber and issuing assertions to communicate with one or more RPs.

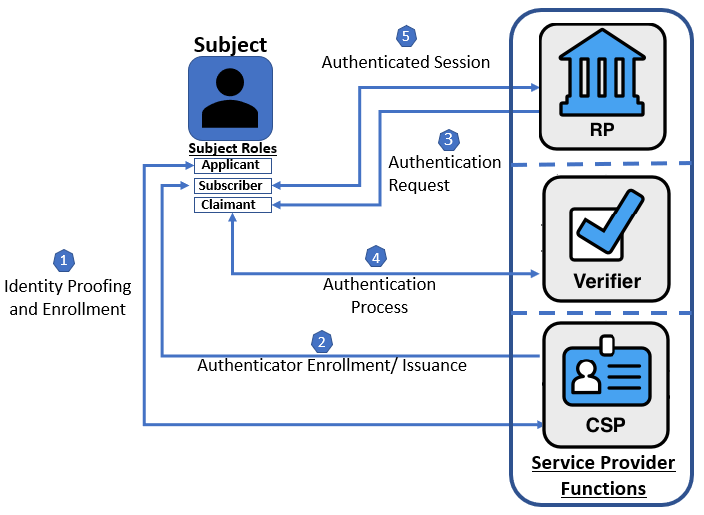

The entities and interactions that comprise the non-federated digital identity model are illustrated in Figure 1. The federated digital identity model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Non-federated Digital Identity Model Example

Figure 1 shows an example of a common sequence of interactions in the non-federated model. Other sequences could also achieve the same functional requirements. The usual sequence of interactions for identity proofing and enrollment activities is as follows:

- Step 1: An applicant applies to a CSP through an enrollment process. The CSP identity proofs that applicant.

- Step 2: Upon successful proofing, the applicant is enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber.

- A subscriber account and corresponding authenticators are established between the CSP and the subscriber. The CSP maintains the subscriber account, its status, and the enrollment data. The subscriber maintains their authenticators.

The usual sequence of interactions involved in using one or more authenticators to perform digital authentication in the non-federated model is as follows:

- Step 3: The RP requests authentication from the claimant.

- Step 4: The claimant proves possession and control of the authenticators to the verifier through an authentication process.

- The verifier interacts with the CSP to verify the binding of the claimant’s identity to their authenticators in the subscriber account and to optionally obtain additional subscriber attributes.

- The CSP or verifier functions of the service provider provide information about the subscriber. The RP requests the attributes it requires from the CSP. The RP, optionally, uses this information to make authorization decisions.

- Step 5: An authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

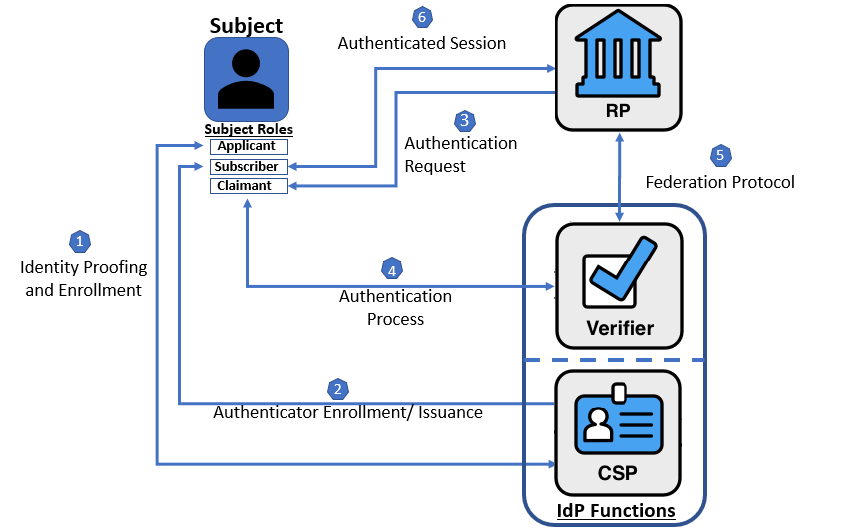

Figure 2. Federated Digital Identity Model Example

Figure 2 shows an example of those same common interactions in a federated model.

- Step 1: An applicant applies to an IdP through an enrollment process. Using its CSP function, the IdP identity proofs the applicant.

- Step 2: Upon successful proofing, the applicant is enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber.

- A subscriber account and corresponding authenticators are established between the IdP and the subscriber. The IdP maintains the subscriber account, its status, and the enrollment data collected for the lifetime of the subscriber account (at a minimum). The subscriber maintains their authenticators.

The usual sequence of interactions involved in using one or more authenticators in the federated model to perform digital authentication is as follows:

- Step 3: The RP requests authentication from the claimant. The IdP provides an assertion and optionally additional attributes to the RP through a federation protocol.

- Step 4: The claimant proves possession and control of the authenticators to the verifier function of the IdP through an authentication process.

- Within the IdP, the verifier and CSP functions interact to verify the binding of the claimant’s authenticators with those bound to the claimed subscriber account and optionally to obtain additional subscriber attributes.

- Step 5: All communication, including assertions, between the RP and the IdP happens through federation protocols.

- Step 6: The IdP provides the RP with the authentication status of the subscriber and relevant attributes and an authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

For both models, the verifier does not always need to communicate in real time with the CSP to complete the authentication activity (e.g., some uses of digital certificates). Therefore, the line between the verifier and the CSP represents a logical link between the two entities. In some implementations, the verifier, RP, and CSP functions may be distributed and separated. However, if these functions reside on the same platform, the interactions between the functions are signals between applications or application modules running on the same system rather than using network protocols.

In all cases, the RP should request the attributes it requires from a CSP or IdP before authenticating the claimant.

The following sections provide more detailed digital identity models for identity proofing, authentication, and federation.

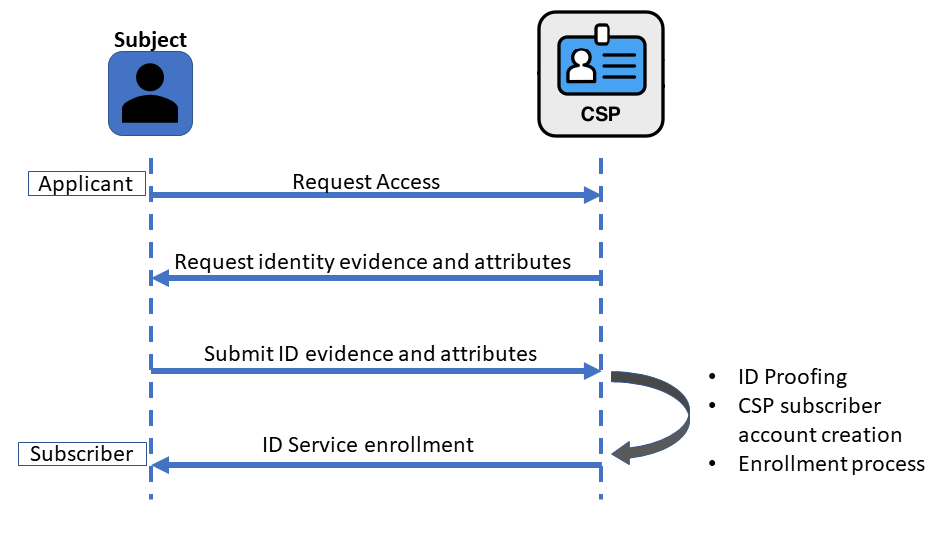

Enrollment and Identity Proofing

The previous section introduced the entities and interactions in the conceptual digital identity model. This section provides additional details regarding the participants’ relationships and responsibilities with respect to identity proofing and enrollment processes.

[SP800-63A], Enrollment and Identity Proofing provides general information and normative requirements for the identity proofing and enrollment processes as well as requirements specific to identity assurance levels (IALs). In addition to a “no identity proofing” level, IAL0, this document defines three IALs that indicate the relative strength of an identity proofing process.

An individual, referred to as an applicant at this stage, opts to enroll with a CSP. If the applicant is successfully proofed, the individual is then enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber of that CSP.

The CSP then establishes a subscriber account to uniquely identify each subscriber and record any authenticators registered (bound) to that subscriber account. The CSP may:

- issue one or more authenticators to the subscriber at the time of enrollment,

- bind authenticators provided by the subscriber, and/or

- bind authenticators to the subscriber account at a later time as needed.

CSPs generally maintain subscriber accounts according to a documented lifecycle, which defines specific events, activities, and changes that affect the status of a subscriber account. CSPs generally limit the lifetime of a subscriber account and any associated authenticators in order to ensure some level of accuracy and currency of attributes associated with a subscriber. When there is a status change or when the authenticators near expiration and any renewal requirements are met, they may be renewed and/or re-issued. Alternately, the authenticators may be invalidated and destroyed according to the CSPs written policy and procedures.

Subscribers have a duty to maintain control of their authenticators and comply with CSP policies in order to remain in good standing with the CSP.

In order to request issuance of a new authenticator, typically the subscriber authenticates to the CSP using their existing, unexpired authenticators. If the subscriber fails to request authenticator re-issuance prior to their expiration or revocation, they may be required to repeat the identity proofing (either complete or abbreviated) and enrollment processes in order to obtain a new authenticator.

Figure 3 shows a sample of interactions for identity proofing and enrollment.

Figure 3. Sample Identity Proofing and Enrollment Digital Identity Model

\clearpage

Authentication and Lifecycle Management

Normative requirements can be found in [SP800-63B], Authentication and Lifecycle Management.

Authenticators

The classic paradigm for authentication systems identifies three factors as the cornerstones of authentication:

- Something you know (e.g., a password)

- Something you have (e.g., an ID badge or a cryptographic key)

- Something you are (e.g., a fingerprint or other biometric characteristic data)

Single-factor authentication requires only one of the above factors, most often “something you know”. Multiple instances of the same factor still constitute single-factor authentication. For example, a user generated PIN and a password do not constitute two factors as they are both “something you know.” Multi-factor authentication (MFA) refers to the use of more than one distinct factor. For the purposes of these guidelines, using two factors is adequate to meet the highest security requirements. Other types of information, such as location data or device identity, may also be used by a verifier to evaluate the risk in a claimed identity but they are not considered authentication factors.

In digital authentication, the claimant possesses and controls one or more authenticators. The authenticators will have been bound with the subscriber account. The authenticators contain secrets the claimant can use to prove they are a legitimate subscriber. The claimant authenticates to a system or application over a network by demonstrating they have possession and control of the authenticator. Once authenticated, the claimant is referred to as a subscriber.

The secrets contained in an authenticator are based on either key pairs (asymmetric cryptographic keys) or shared secrets (including symmetric cryptographic keys and memorized secrets). Asymmetric key pairs are comprised of a public key and a related private key. The private key is stored on the authenticator and is only available for use by the claimant who possesses and controls the authenticators. A verifier that has the subscriber’s public key, for example through a public key certificate, can use an authentication protocol to verify the claimant has possession and control of the associated private key contained in the authenticators and, therefore, is a subscriber.

As mentioned above, shared secrets stored on an authenticator may be either symmetric keys or memorized secrets (e.g., passwords and PINs). While both keys and memorized secrets can be used in similar protocols, one important difference between the two is how they relate to the claimant. Symmetric keys are generally chosen at random and are complex and long enough to thwart network-based guessing attacks, and stored in hardware or software that the subscriber controls. Memorized secrets typically have fewer characters and less complexity than cryptographic keys to facilitate memorization and ease of entry. The result is that memorized secrets have increased vulnerabilities that require additional defenses to mitigate.

There is another type of memorized secret used as an activation factor for a multi-factor authenticator. These are referred to as activation secrets. An activation secret is used to decrypt a stored key used for authentication or is compared against a locally held stored verifier to provide access to the authentication key. In either of these cases, the activation secret remains within the authenticator and its associated user endpoint. An example of an activation secret would be the PIN used to activate a PIV card.

As used in these guidelines, authenticators always contain or comprise a secret; however, some authentication methods used for in-person interactions do not apply directly to digital authentication. For example, a physical driver’s license is something you have and may be useful when authenticating to a human (e.g., a security guard) but it is not an authenticator for online services.

Some commonly used authentication methods do not contain or comprise secrets, and are therefore not acceptable for use under these guidelines. For example:

- Knowledge-based authentication, where the claimant is prompted to answer questions that are presumably known only by the claimant, does not constitute an acceptable secret for digital authentication.

- A biometric also does not constitute a secret and can not be used as a single-factor authenticator.

A digital authentication system may incorporate multiple factors in one of two ways:

- The system may be implemented so that multiple factors are presented to the verifier, or

- Some factors may be used to protect a secret that will be presented to the verifier.

For example, item 1 can be satisfied by pairing a memorized secret (something you know) with an out-of-band device (something you have). Both authenticator outputs are presented to the verifier to authenticate the claimant. For item 2, the authenticator and authenticator secret could be a piece of hardware that contains a cryptographic key (something you have) that is controlled by the claimant where access is protected with a fingerprint (something you are). When used with the biometric factor, the cryptographic key produces an output that is used to authenticate the claimant.

As noted above, biometrics do not constitute acceptable secrets for digital authentication and, therefore, cannot be used for single-factor authentication. However, biometrics authentication can be used as an authentication factor for multi-factor authentication when used in combination with a possession-based authenticator. Biometric characteristics are unique, personal attributes that can be used to verify the identity of a person who is physically present at the point of verification. This includes, but is not limited to, facial features, fingerprints, iris patterns, and voiceprints.

Subscriber Accounts

As described in the preceding sections, a subscriber account binds one or more authenticators to the subscriber via an identifier as part of the registration process. A subscriber account is created, stored, and maintained by the CSP. The subscriber account records all identity attributes validated during the identity proofing process.

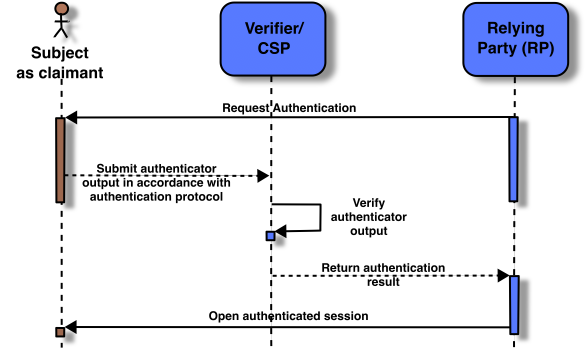

Authentication Process

The authentication process enables an RP to trust that a claimant is who they say they are. Figure 4 shows a sample authentication process. Other approaches are described in [SP800-63B], Authentication and Lifecycle Management. This sample authentication process shows interactions between the RP, a claimant, and a verifier/CSP. The verifier is a functional role and is frequently implemented in combination with the CSP, as shown in Fig. 4, the RP, or both.

Figure 4. Sample Authentication Process

A successful authentication process demonstrates that the claimant has possession and control of one or more valid authenticators that are bound to the subscriber’s identity. In general, this is done using an authentication protocol involving an interaction between the verifier and the claimant. The exact nature of the interaction is extremely important in determining the overall security of the system. Well-designed protocols can protect the integrity and confidentiality of communication between the claimant and the verifier both during and after the authentication, and can help limit the damage that can be done by an attacker masquerading as a legitimate verifier.

Additionally, mechanisms located at the verifier can mitigate online guessing attacks against lower entropy secrets — like passwords and PINs — by limiting the rate at which an attacker can make authentication attempts, or otherwise delaying incorrect attempts. Generally, this is done by keeping track of and limiting the number of unsuccessful attempts, since the premise of an online guessing attack is that most attempts will fail.

Federation and Assertions

Normative requirements can be found in [SP800-63C], Federation and Assertions.

In general usage, the term federation can be applied to a number of different approaches involving the sharing of information between different trust domains. These approaches differ based on the kind of information that is being shared between the domains. Some common examples include:

- sharing identifiers (e.g., using a driver’s license number or an email address),

- sharing authenticators (e.g., using a PKI authenticator for multiple applications),

- sharing identity assertions (e.g., a federation protocol like OpenID Connect or SAML),

- sharing account attributes (e.g., a provisioning protocol like SCIM), and

- sharing authorization decisions (e.g., a policy protocol like XACML).

The SP 800-63 guidelines are agnostic to the identity proofing, authentication, and federation architectures an organization selects and they allow organizations to deploy a digital identity scheme according to their own requirements. However, there are scenarios that an organization may encounter that make federation potentially more efficient and effective than establishing identity services local to the organization or individual applications. The following lists detail scenarios where the organization may consider federation a viable option. These lists are provided for consideration and are not intended to be comprehensive.

An organization should consider accepting federated identity assertions if any of the following apply:

- Potential users already have an authenticator at or above the required AAL.

- Multiple types of authenticators are required to cover all possible user communities.

- An organization does not have the necessary infrastructure to support management of subscriber accounts (e.g., account recovery, authenticator issuance, help desk).

- There is a desire to allow primary authenticators to be added and upgraded over time without changing the RP’s implementation.

- There are different environments to be supported, as federation protocols are network-based and allow for implementation on a wide variety of platforms and languages.

- Potential users come from multiple communities, each with its own existing identity infrastructure.

- The ability to centrally manage account lifecycles, including account revocation and binding of new authenticators is important.

An organization should consider accepting federated identity attributes if any of the following apply:

- Pseudonymity is required, necessary, feasible, or important to stakeholders accessing the service.

- Access to the service requires a partial attribute list.

- Access to the service requires at least one derived attribute value.

- The organization is not the authoritative source or issuing source for required attributes.

- Attributes are only required temporarily during use (such as to make an access decision), and the organization does not need to retain the data.

Federation Benefits

Federated architectures have many significant benefits, including, but not limited to:

- Enhanced user experience: For example, an individual can be identity proofed once and reuse the subscriber account at multiple RPs.

- Cost reduction to both the user (reduction in authenticators) and the organization (reduction in information technology infrastructure).

- Minimizing data in applications as organizations do not need to collect, store, or dispose of personal information.

- Minimizing data exposed to applications, using pseudonymous identifiers and derived attribute values instead of copying account values to each application.

- Mission enablement: Organizations can focus on their mission without worrying about expending resources on identity management.

The following sections discuss the components of a federated identity architecture should an organization elect this type of model.

Federation Protocols and Assertions

Federation protocols allow for the conveyance of assertions, authentication attributes, and subscriber attributes across networked systems. In a federation scenario, as shown in Figure 2, the CSP provides a service known as an identity provider, or IdP. The IdP acts as a verifier for authenticators issued by the CSP. Using federation protocols, the IdP sends a message, called an assertion, about this authentication event to the RP. Assertions are verifiable statements from an IdP to an RP that represent an authentication event for a subscriber. The RP receives and uses the assertion provided by the IdP, but the RP does not verify authenticators directly.

Federation is generally used when the RP and the IdP are not a single entity or are not under common administration, though this technology can be applied within a single security domain for a variety of reasons. The RP uses the information in the assertion to identify the subscriber and make authorization decisions about their access to resources controlled by the RP.

Examples of assertions include:

- Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) assertions are specified using a mark-up language intended for describing security assertions. They can be used by a verifier to make a statement to an RP about the identity of a claimant. SAML assertions may optionally be digitally signed.

- OpenID Connect claims are specified using JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) for describing security, and optionally, user claims. JSON user information claims may optionally be digitally signed.

- Kerberos tickets allow a ticket-granting authority to issue session keys to two authenticated parties using symmetric or asymmetric key establishment schemes.

Relying Parties

An RP relies on results of an authentication protocol to establish confidence in the identity or attributes of a subscriber for the purpose of conducting an online transaction. RPs may use a subscriber’s federated identity (pseudonymous or non-pseudonymous), IAL, AAL, FAL, and other factors to make authorization decisions.

When using federation, the verifier is not a function of the RP. A federated RP receives an assertion from the IdP, which provides the verifier function, and the RP ensures that the assertion came from an IdP that is trusted by the RP. The RP also processes any additional information in the assertion, such as personal attributes or expiration times. The RP is the final arbiter concerning whether a specific assertion presented by a verifier meets the RP’s established criteria for system access regardless of IAL, AAL, or FAL.